The National Park System represents one of the largest and best-known examples of environmental protection in the United States, but from Acadia to Zion, the popular version of this story begins with a familiar figure: , often ending up with a familiar figure (well, Theodore Roosevelt) championing the grandeur of its landscapes.

In reality, of course, these wonderful places were known and cherished long before ranger stations welcomed the lines of cars that rolled into them on busy summer days. All 63 national parks are located on former indigenous lands. And for thousands of years, before the creation of the National Park Service, people carefully managed these ecosystems and managed these resources.

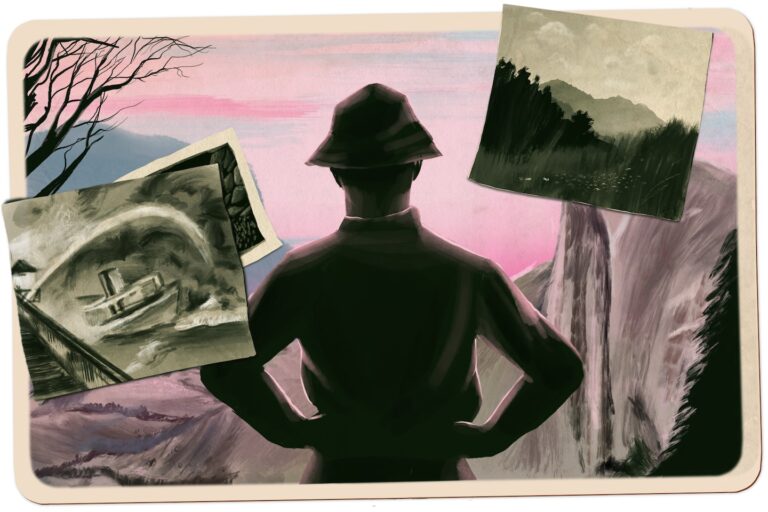

In the course of researching and reporting for the Post’s podcast “Field Trip,” I learned how more than 150 years of land management efforts are changing how these fragile and dynamic landscapes are protected into the future. We discovered many people who contributed. Among them, I would like to introduce seven that captivated me with their unique contributions.

George Melendez Wright, one of the first Hispanic park rangers, was studying zoology at the University of California, Berkeley, and was appalled by what he saw in Yosemite in the 1920s. It turned out that the National Park Service was feeding bears out of trash cans for the entertainment of visitors. Park officials were also killing mountain lions as part of a broader predator eradication effort across U.S. public lands.

Jerry Emory, author of the biography “George Melendez Wright: The Fight for Wildlife and Wilderness in National Parks,” said, “To him, it was completely unnatural and contrary to the reason national parks were created.” ” he said.

Although still in his early 20s, Wright became one of the first major investigators of wildlife in national parks. In addition to Yosemite, he used his personal funds to fund the National Park Service’s first coordinated wildlife survey and traveled throughout the western United States. He recorded these findings in a seminal report called “Fauna No. 1.”

In 1933, the National Park Service appointed Wright to lead its new wildlife division, which also made him the first Hispanic person to hold a leadership role within the agency. A few years later, at the age of 31, he died in a car accident while leaving what would become Big Bend National Park in Texas.

Despite his short career, Wright’s recommendations laid the foundation for many of the core wildlife conservation policies adopted by the Park Service.

Mardy Murie echoed Wright’s efforts in many ways, advocating for the National Park Service to make wildlife a top priority and protect ecosystems for themselves.

“For wildlife conservation to be successful, we need to protect the land,” said Bill Meadows, past president of the Nature Conservancy. “And she knew it.”

Mury initially found her way into conservation through her husband, Olaus Mury, a prominent wildlife biologist who studied the migration of elk and caribou. Together, they have become a vocal advocate for both adding new areas to the national park system, such as Grand Teton, and redrawing the boundaries of existing national parks to keep the entire ecosystem intact. became.

The Muley’s 1956 expedition to northeast Alaska helped convince President Dwight D. Eisenhower to establish what is now called the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. After her husband’s death in 1963, Ms. Muley was the founder of a bill (later passed by Jimmy Carter in 1980) that turned vast swathes of Alaska into federally protected lands and doubled the total area managed by the National Park Service. began lobbying for a bill signed by the president. And in 1998, at age 96, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in recognition of her decades of wildlife conservation work.

“She was in awe of her husband and the people around her, and she grew to a point where people were in awe of her,” Meadows said.

While many know about the work of Ansel Adams and the role his stunning landscape photography played in preserving Yosemite National Park, similar efforts were made on the other side of the country around the same time. Very few people know that.

George Masa, a Japanese immigrant living in North Carolina in the 1920s, spent years hiking deep into the woods with a large-format camera to document the beauty of the Great Smoky Mountains. He recorded storm clouds gathering over the rugged mountain ridges and the sun’s rays shining brightly. A quiet lake.

“Anyone who has spent time in the Smoky Mountains knows fog and rain,” says Janet McCue, co-author of a forthcoming biography of Masa. “Unless you go there, you won’t realize how difficult it is to take photos of them, and how hard Masa worked to capture those views.”

At a time when trails were few and far between, equipment was very heavy, and even modest photographs required precise conditions, Masa was able to create images that evoked a national respect for Appalachia. His photos were accompanied by numerous articles advocating for the protection of the Smokies from the logging industry. They played a key role in persuading President Calvin Coolidge and Congress to establish the Great Smoky Mountains as a national park, and they also gave donors like the Rockefellers millions of dollars to buy the land. He also played an important role in persuading people to buy and deliver the goods. to the federal government.

Nearly 100 years after Masa hiked among the oaks and hemlocks, Great Smoky Mountains National Park is now the most popular of all 63 national parks in the system. In 2023, more than 13 million people have visited and experienced the same magic in an ever-changing forest. “Masa captured that better than anyone,” McCue said.

For national park enthusiasts, Polly Dyer’s name is synonymous with environmental activism in the Pacific Northwest. Since the 1950s, she has become a leading champion of the region’s natural wonders, from its dramatic coastline to its temperate rainforests and subalpine grasslands.

“Polly was a very strong, clear and forceful advocate of doing the right thing,” said Destry Jarvis, former deputy director of the National Park Service. “She had a presence.”

In 1953, Dyer’s persuasive powers were able to halt efforts to open parts of Olympic National Park to logging. In 1958, she also helped stop a road project in the park that would have damaged miles of Pacific coastline.

As a founding member of the North Cascades Conservation Council, she convinced members of Congress to create North Cascades National Park in 1968, protecting more than 500,000 acres of mountains, glaciers, and alpine forests.

“There was significant opposition to the creation of North Cascades,” Jarvis said. But, he added, “she was very persistent.”

Few conservation laws are as important as the Wilderness Act, which created high levels of protection for some of the most pristine areas in the United States. Howard Zernizer envisioned this plan, wrote the bill, and supported it.

Mr. Zerniser, who worked for the Nature Conservancy, joined the effort to stop the construction of a dam within Dinosaur National Monument, a landscape of rivers, deserts and canyons on the Colorado-Utah border in 1956. drafted this bill. Through his political struggles, he became convinced that better legal safeguards should exist to protect land from development.

However, the road to enacting the Nature Conservation Act was a long one. Mr. Zernizer will spend eight years revising the language of potential legislation. He wrote 66 drafts of his before Congress finally passed it in 1964. That was just a few months after his death.

“He never gave up,” said Meadows, a former Nature Society president. “And he did it through words. Some call it the most lyrical bill ever passed.”

Thanks to the Conservation Act, more than 100 million acres of land (much of it within national parks) is now used for industrial projects such as dams, as well as basic infrastructure such as visitor centers, roads, and even campgrounds. All development, including

Designated nature preserves currently cover more than 80 percent of all land managed by the National Park Service. Therefore, even though visitor numbers to the national park continue to increase, much of its ecosystem remains protected from undue human influence.

“This affected the composition of the Park Service,” Meadows said. “It really established the value that parks need to be protected, not just open to the public.”

Carl Stokes was the mayor of Cleveland and the first black mayor elected in a major U.S. city when the Cuyahoga River caught fire in 1969 due to pollution. A Time magazine article from the summer of that year described the river as “chocolate-colored and oily, bubbling with underground gas, oozing rather than flowing.”

Although the fire caused relatively little damage, Stokes used the incident to draw national media attention to environmental dangers facing urban and minority communities, including a lack of clean water. contributed to that. His outspokenness about the status of the Cuyahoga River helped push for the Clean Water Act years later, and also laid the groundwork for the nearby Cuyahoga Valley to be managed by the National Park Service as a national recreation area starting in 1974. I was there. (This national park later became the rare national park to have Superfund sites within it.)

Still, on the first Earth Day, held less than a year after the Cuyahoga River fires, Stokes also said that current environmental efforts “are coming at the expense of other priorities that affect low-income communities.” ”, he complained. An early voice in the environmental justice movement, Stokes convinced people that urban places deserved as much protection as remote areas of pure beauty.

The National Park Service manages approximately 400 areas in addition to 63 large national parks. These include sites of historical and environmental significance, such as Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in Montana, the site of a famous decisive battle between the U.S. military and several Plains Indian tribes. I am.

For nearly 50 years, the Custer Battlefield National Monument has been named in memory of the Army officers and their units on the losing side of the battle. And he began the process of changing its name in 1989, with Barbara Sutter becoming the site’s first Native American director. This work will continue under the direction of Gerald Baker, a member of the Mandan Hidatsa Tribe of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, with an official name change and changes to make the park unit more inclusive of Indigenous perspectives. Both oversaw several additional efforts to.

“For the first time, he really recognized his natural role, his natural presence, his natural influence,” said Jarvis, a former assistant park service director. “And that was a huge turnaround for the Park Service.”

In 2004, Baker became the first Indigenous director of Mount Rushmore, another park management facility, where he helped bring long-hidden Indigenous history to the surface. (The Black Hills, where the faces of four presidents are carved into the rock, are very sacred to the Lakota and his Sioux tribes.)

Indigenous peoples were the original environmental custodians of all the lands that now make up the national park system. There is now greater effort within the National Park Service to recognize that fact and better incorporate Indigenous knowledge into park management. In 2021, Charles Sams III was appointed the first Native American to head the National Park Service.

“We’re seeing the Park Service opening its doors even wider,” Jarvis said. “Gerard was the first one to actually set that whole movement in motion.”