European voters are being disheartened by last-minute social media campaigns. Euronews looks at some EU countries where the phenomenon has been observed and whether it has worked.

advertisement

The European Parliament warned on Wednesday that a last-minute campaign was spreading on social media platforms aimed at dissuading people from voting in this week’s European Parliament elections.

We look at some examples widespread across the European Union and consider whether they are effective.

Italy: Stay at home

An abstention movement seems to be spreading in Italy. With the hashtags #iononvoto (I won’t vote) and #iorestoacasa (I stay at home), thousands of X users are signaling their intention to not take part in the elections and to reject the political system. According to a spokesman for the European Parliament, which identified and reported the movement, the aim of the movement is to dissuade other citizens from going to the polls this Saturday and Sunday.

“This is a story we’ve seen repeatedly in past elections. [that] “The elections will no longer be free and fair,” the spokesperson said on Thursday. The hashtag has indeed been used previously for national votes in 2014 and 2022.

The posts are often accompanied by photo and video montages mocking politicians and political parties. The content varies, but common themes include rejection of the EU, hostility towards migrants, distrust of vaccines and the refusal to send Italian troops to help Ukraine (implying possible Russian interference).

Germany: Please check the box (right)

German voters were shocked when a video was posted on TikTok with instructions on how to mark their ballot when voting in the European Parliament elections. The post warns that any cross that fits inside the circle is correct and will be counted, but any cross that goes beyond the edge of the circle is incorrect and will be invalid. Euronews reports that it is claimed to be a plot against Germany’s far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD).

According to the fake news, election officials will check that AfD-only votes fit inside the circle and do not go beyond the margins – if they do not, they will be considered invalid. However, German election law allows voters to put a cross inside the circle or vote in “any other way.”

Another issue with postal voting also caused confusion. Some of X’s messages claimed that ballots with corners cut off were invalid. This is also false: German election law requires that postal ballots have their corners cut off to accommodate the visually impaired.

Spain and France: Invalidated votes

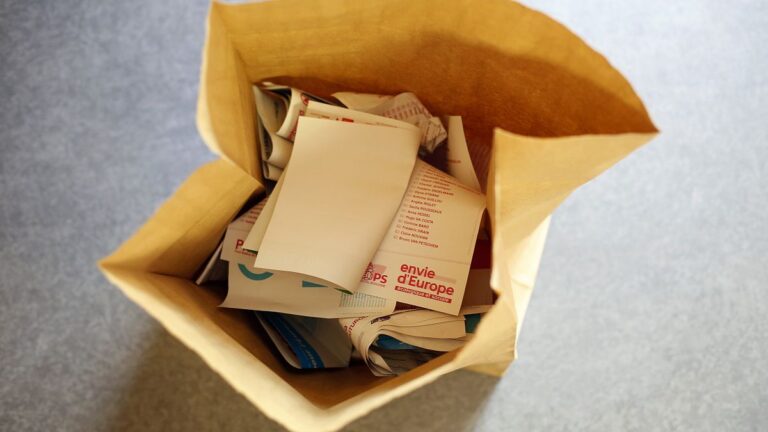

Disinformation is not necessarily organised from abroad, but can also result from the activities of individuals with the intention of humour or deception. Several Spanish users shared with their followers a “technique” that supposedly allows “double voting”, claiming that by placing two ballots in an envelope with a handwritten note on turnout, it is possible to split the vote between two political parties.

This trick doesn’t work, because it makes the vote invalid. The attached photos always show a split between the People’s Party (PPE) and Vox (ECR) votes, and come from accounts of users who previously supported left-wing positions, which shows that the aim is to deceive right-wing voters.

In France, where pro-Palestinianism is a key campaign theme for the far-left party Indomitable France, opponents of the party suggested adding a picture of the Palestinian flag to ballot papers to show support. Whether in jest or malice, this misleading suggestion was taken seriously by some X-users and party officials, including MP Manuel Bompard, who accused the tweeter of “trying to mislead voters, which will result in invalid votes.”

Foreign interference

In addition to these efforts to sow chaos at home, foreign misinformation about the EU has surged to record levels.

The European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent fact-checking network, published findings on Tuesday showing that disinformation about EU policies and institutions made up 15% of all cases detected in May, the highest figure since it began tracking EU disinformation in 2023.

But Meta, which owns Instagram and Facebook, said in a threat report published late last month that malicious attempts to influence users on its platforms were primarily focused on local elections, rather than the upcoming European Parliament elections. The tech giant said it had seen no evidence that such groups were gaining traction among users.