Image credit: Getty Images

Article information Author: Flora Drury Role: BBC News

4 hours ago

When planning a vacation, Afghanistan isn’t high on most people’s list of must-visit destinations.

Decades of conflict have meant few tourists have dared to set foot in the Central Asian country since its heyday as part of a hippie trail in the 1970s, and the Taliban’s return to power in 2021 has thrown the future of its surviving tourism industry into further uncertainty.

But a quick scroll through social media shows that tourism has not only survived, but is thriving in its own very niche way.

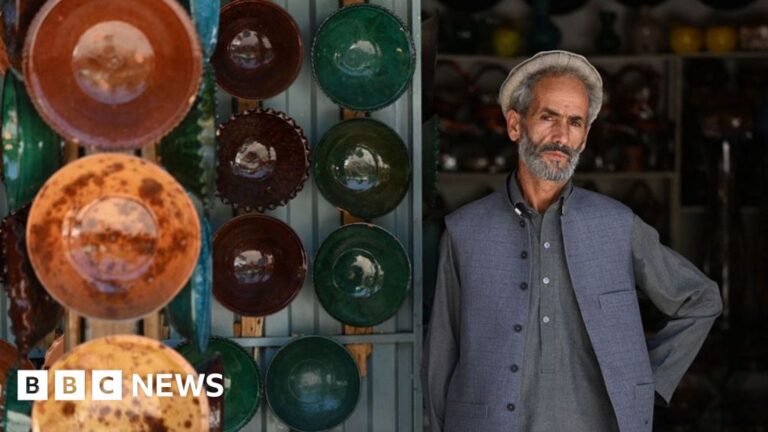

“5 reasons why you should choose Afghanistan as your next travel destination,” the influencers say with glee, taking in the sparkling lakes, mountain passes and colorful, bustling markets.

“Afghanistan has not been safer in 20 years,” one said, posing next to a vast trench that was created after the Bamiyan Buddhas were destroyed more than two decades ago.

A people struggling to survive, or a regime hell-bent on changing the narrative in its own favour?

“It’s very ironic to see videos on TikTok of Taliban guides and Taliban officials handing out tickets to tourists. [site of the] “The destruction of Buddha statues,” said Dr Falconde Akbari, whose family fled Afghanistan during the first Taliban regime in the 1990s.

“These are the people who destroyed the Buddha.”

“It’s just raw.”

At first glance, the list of countries Sacha Heaney has visited doesn’t sound like ideal holiday destinations – places that many of us are used to reading about in the news.

But it seems that’s exactly why Heaney, and thousands of others like her around the world, chose this spot: secluded, about as far away from five-star resorts as you can get, and therefore almost completely unique.

“It’s just so raw,” says the part-time travel guide from Brighton, England. “There are very few places more raw than that, and that can be appealing, if you want to see real life.”

What would the Taliban gain from that? After all, they have a reputation for being highly suspicious, even hostile, towards outsiders, especially Westerners.

Still, they pose a little uncomfortably next to tourists, showing off their guns, and their bearded faces are going viral with the kind of momentum that would see them go viral on TikTok (which will be banned in the country from 2022).

Image credit: Getty Images

Image caption: Seven-day tours with international operators cost thousands of dollars

In one sense, the answer is simple: Nearly isolated internationally, subject to widespread sanctions and denied access to funds given to Afghanistan’s former government, the Taliban need money.

Most seem to be joining one of the myriad tours offered by international companies that offer a glimpse into the “real Afghanistan” for a few thousand dollars per trip.

Mohammed Saeed, head of tourism for the Taliban government in Kabul, said earlier this year that he dreams of making the country a popular tourist destination, with a particular focus on the Chinese market — all with the support of “the elders.”

“What they want to do is [with tourism]”It’s OK,” says Rohullah, an Afghan tour guide whose smiling face has been shared dozens of times by happy customers since he started leading groups three years ago.

“Tourism creates a lot of jobs and opportunities,” he added. And he should know that.

Image credit: Getty Images

Image caption: One of the highlights of the tour is visiting the spot where the Great Buddha once stood

After what he calls “the change” in 2021 — the U.S. withdrawal and the Taliban’s seizure of power — he was approached by a friend for a job as a tour guide. Prior to that, he had worked for the Afghanistan Ministry of Finance for eight years.

And he doesn’t regret it: Tour groups like Heaney’s need drivers and local guides, and with tourist numbers continuing to grow, there’s no shortage of work.

It is no surprise then that a group of young men – all male – are attending Taliban-sanctioned hospitality courses in Kabul, hoping to cash in on the burgeoning hospitality industry.

“We have high hopes for this year,” Rohara said. “It’s a time of peace. Before it wasn’t possible to travel throughout Afghanistan, but now it really is possible.”

The killing of three Spanish tourists and one Afghan by Islamic State-linked militant group ISK in a Bamiyan market in May stood out as an unusual case targeting foreigners.

The British Foreign Office continues to advise against travel to the country, which remains a target of attacks. According to the Counterterrorism Center at West Point, ISK carried out 45 attacks in 2023 alone.

Of course, one of the reasons Afghanistan is now more secure is because the Taliban themselves were responsible for much of the violence during the two decades of war that engulfed the country after the U.S. invasion.

For example, in the first three months of 2021, the UN attributed more than 40% of the 1,783 recorded civilian deaths to the Taliban. But they are not alone: The same report noted that 25% of the deaths in the same period were attributable to U.S.-led Afghan government forces.

Know the rules and learn the game

Perhaps more surprising is that Heaney and two other members of the group she led with Lupin Tours earlier this year were women. And they were far from the only ones: Young Pioneer Tours, which has long experience organising holidays to North Korea and other off-the-grid destinations, also runs women-only trips to Afghanistan. Lohara has guided solo female travelers “without a problem.”

The Taliban impose strict rules on women in their country, excluding them from the workplace, secondary education and even banning them from Band-e-Amir National Park, a stop on many international tours, but they do not ban female tourists from visiting.

That means “women and men meet differently” in Afghanistan, acknowledges Rowan Beard, who has run his organization in the country since 2016. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, he argues.

“Men can’t talk to women, but women can,” he explains. “Our female tourists had the opportunity to sit with a group of women and hear their experiences and further insights about the country.”

But everyone has to follow certain rules, and Heaney and her group were told in advance what they needed to do to do so: how to dress, how to behave, who they could and couldn’t talk to.

The Taliban were an ever-present presence, standing by with guns and among those who would not speak to Heaney or the female members of her group, something she took no umbrage at.

“You have to know the rules and learn the game,” she explains.

Image credit: Getty Images

Image caption: The Buddha statue, which was visited by tourists in the 1970s, was destroyed during the first Taliban regime.

For Heaney, speaking to the women the group visited and who were “incredibly happy” was the highlight of a tour that highlighted the “truly lovely”, generous and welcoming people of Afghanistan.

Videos posted to social media show women conspicuously missing from the bustling cityscape, a fact some visitors dismiss as being simply in the stores doing what women around the world love to do: shop.

“Concealing our suffering”

These slick videos from outside Afghanistan leave some bitter.

“[Tourists think] “This is simply a backward part of the world and they don’t care what they do. We don’t care,” said Dr Akbari, now a postdoctoral researcher at Monash University in Australia.

“We just go and enjoy the view and hear opinions and preferences. That’s what really hurts us.”

She added that this was “unethical tourism lacking political and social awareness” and allowing the Taliban to whitewash the realities of life now that they have returned to power.

For perhaps this is another value of tourism for the Taliban: a new image: one that de-emphasizes the rules that govern the lives of Afghan women.

Image caption: While Western women can travel relatively freely within the country, Afghan women cannot

“My family does not have a male guardian, so I cannot move from one district to another,” Dr. Akbari points out. “We are talking about 50 percent of the population having no rights… We are talking about a regime that implemented gender apartheid.”

“Yes, there is a humanitarian crisis. It’s nice that tourists can go to the shops and buy something, which might help local families, but at what cost? The normalization of the Taliban regime.”

Heaney acknowledges that before the visit he had a “moral dilemma” about the Taliban’s stance on women.

“Of course I feel very strongly about their rights. The thought has crossed my mind,” she said, “but as a tourist… I think countries are worth visiting and should be listened to. We have a warped view. I want to see with my own eyes so I can judge for myself.”

Beard argues that there is “no one-size-fits-all answer” to what women experience in the country and that people should be allowed to draw their own conclusions.

Marina Novelli, professor of marketing and tourism at the University of Nottingham Business School, said the overly positive views of some people shared on social media were undoubtedly problematic.

“I’m very wary of sensationalising destinations,” she says, explaining that some people might “paint a naive picture”.

“Travellers sometimes want to send a positive message, but that’s not the problem. [aren’t still there].”

Image credit: Getty Images

Image caption: Since the Taliban came to power, women’s rights, including their ability to work, have been severely restricted.

Prof Novelli, who sits on the International Tourism Ethics Commission, argues that boycotts are not the way forward either.

“I think that’s a problem because it further isolates these countries.”

It also raises the question of where to draw the line: There are many tourist destinations in the Northern Hemisphere where government practices are questionable, she said.

But the potential benefits are also worth considering: Saudi Arabia’s growing tourism industry is expanding women’s role in society, she said.

“I believe tourism can be a force for peace and intercultural exchange,” says Professor Novelli.

But that prospect is far from easy for women like Dr Akbari and her family and friends in Afghanistan.

“Our pain and suffering are being masked with the false security that the Taliban want,” she said.