The spider is a weaver. Navajo artist and weaver Melissa Cody knows this clearly. As she sits cross-legged on the sheepskin of the loom, a stack of monumental tapestry brings the gift of loom and weaving to one of the wooden platforms that pushes her higher as it grows. The sacred knowledge of Spider-Woman and Spider-Man emerges. Diné, who is Navajo, is in the studio with her.

It also incorporates the first major solo exhibition of the artist’s work, “Melissa Cody: Webbed Sky,” held at the Museo Nacional de São Paulo (commonly known as MASP) in Brazil.

This exhibition marks a milestone in the recognition of Indigenous artists by museums and other institutions, from the recent retrospective of Joan Quick to Sea Smith’s work at the Whitney Museum to the expansion of the artist’s roster at the Venice Biennale. This is part of a belated recognition. Cody, 41, is a millennial at the forefront of an art form that harks back thousands of years, building on tradition but willing to go beyond it.

The title of her show alludes to her 2021 work “Under Cover of Webed Skies.” In this work, an hourglass shape resembling the underbelly of a spider takes the place of the artist himself, transmitting the wisdom of Spider-Woman to the next generation and the web of maternal protection from the mountains to the sky. (Selected works will also be on display at the Garth Greenan Gallery from April 25th to June 15th.)

Cody was weaned from weaving, using the same wooden comb he started with when he was 5 years old, beating the weft for a 9-foot-tall piece of fabric. She grew up on the western edge of the Navajo Nation in Arizona as her fourth generation of her family. Most notable among the notable female weavers is her award-winning mother, Laura S. Cody, who made her own churro sheep to create traditional patterns such as “Two Gray Hills.” Her grandmother, Martha Gorman Schultz, continued to pioneer the field with outdoor looms into the 1990s. .

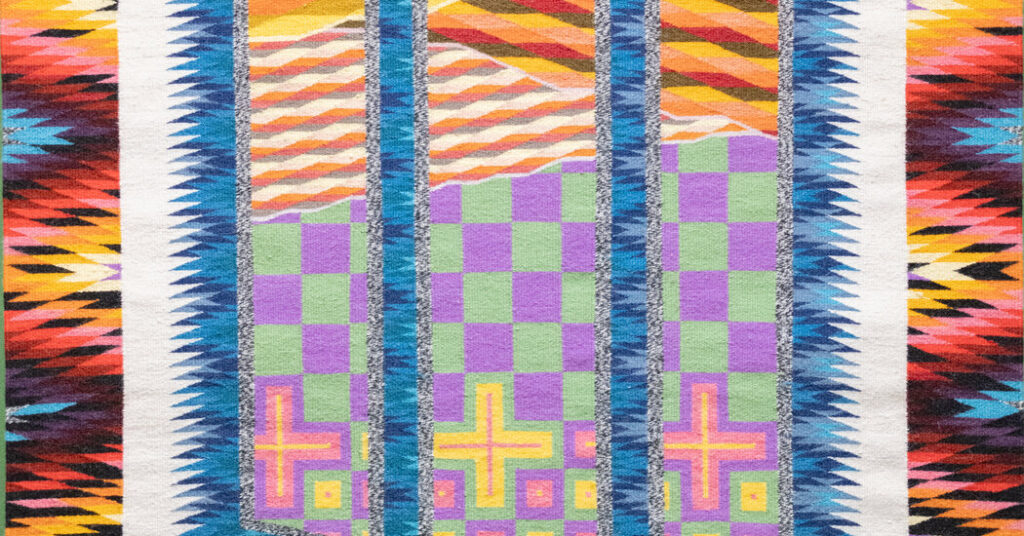

Cody’s complex, multidimensional canvases, or what she calls “atmospheres,” are layered with past, present, and future histories, including her own. Describing herself as “the voice of kids who grew up in the ’80s,” she often incorporates imagery and typography from early video games like Pac-Man and Pong, enlarging individual pixels to create makes the surface appear to be moving smoothly. Her tapestry becomes her own life force.

Her textiles are worlds within worlds, tweaking perspective and juxtaposing ancient and modern motifs in an electric palette of aniline-dyed threads. There’s a reason why her patterns are called “dazzling” – the dizzying Diné of bright serrated diamonds that Cody admires.

In one stunning piece, “Into the Depths, She Rappels,” the iconic Spider-Woman descends into a shocking fuchsia abyss with a single thread. There, animated rainbow-colored pixels appear ready to face off against a dizzying horde of enemies.

“Hundreds of years ago, Navajo weavers played with illusions by layering and layering motifs to create 3D effects,” says the cultural anthropologist and former curator who works with artists. says Anne Lane Hedlund. “Melissa took it to new territory.”

She has mastered the art of slow in a fast world.

Cody’s vibrant Germantown Revival color palette evokes the dark times, the annihilation of 1863-1866 that wiped out the Diné people by burning villages, killing herds, and driving more than 10,000 Navajos from their homeland. It was born out of a US government campaign. The Navajos were forced to march hundreds of miles to Bosque Redondo, Fort Sumner, in present-day New Mexico, where they were imprisoned. So in an act of creative resistance, the women unraveled government-issue synthetic dyed wool blankets made in Germantown, Pennsylvania, and re-knitted them with their own designs, overcoming trauma and loss with sheer perseverance and beauty. I did.

Over the next several decades, white trading post owners persuaded many Diné weavers to limit themselves to “authentic” weaving using natural yarns tied to specific Navajo communities. Some non-Native scholars followed suit, dismissing his aniline-dyed Germantown revival style as inauthentic.

Cody developed an early love for color and an eclectic aesthetic, inspired by a collection of dizzyingly bold yarns gifted to her by a friend.

She describes the town of Leup, Arizona, where she grew up, as “a desolate Mars-like place” with towering red rocks, dunes and mesas. Her parents’ home had no running water and was lit with kerosene, and only when her father Alfred, a professional carpenter, turned on the gas generator could she watch an hour of static television.

Cody thought every little girl had a loom, her mother recalled. Little Melissa and her older sister Reinalda, along with her grandmother Martha and her inventive aunt Marilou Schultz, are involved in major art shows at venues such as the Heard Museum of Art in Phoenix and the Santa Fe Indian Market. visited frequently. A microprocessor commissioned by Intel and translated in wool is now on display at the National Gallery.

Many shows had youth divisions, and Cody often competed against his younger sister, half-Hopi cousin, and his male cousins. (Diné weavers are traditionally women.) “I wanted to be as good as her,” she said of her sister. Cody won her first ribbon at the Santa Fe Indian Market when she was eight years old. This reflects the inner urge that kept her glued to her loom even after school or while watching Saturday morning cartoons.

She credits her mother, who had a loom in the living room, with “instilling independence in what I made.”

“She introduced me to a more advanced, technically precise level of work that didn’t use a lot of negative space and was filled with geometric patterns from top to bottom,” she explained. “When I asked her about her color and whether she liked it, she said, ‘Do you like her? “What do you think about that?” So there was a lot of reflection.”

Cody has perfected traditional techniques over the years, which has given him the confidence to experiment and create more personal pieces. “It’s, ‘What is the emotion I’m trying to convey?'” she said. “What’s the theory behind that?”

Some of her most ambitious works depict responses to personal crises. In 2015, her anguish over the sudden death of her 38-year-old fiancé, in block letters, included an excerpt from Rat Pack crooner Dean Martin’s “Sweet Sweet Loveable You.” I decided to create an unusual textile.

Her father’s diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease led to similar advances in “dopamine regression.” In one of the series, a hallucinating illusionist changes direction, partially overlaid with an abstracted black Spider-Woman cross. The bold red cross, synonymous with medicine, extends into a rainbow, a symbol of the presence and blessings of holy people. “That’s her way of coping,” her mother said. “That’s how she expresses her thoughts.”

However, not all curators can relate to Cody’s boundary-breaking tapestry. “She’s spicy,” said Marcus Monerquit, director of community engagement at the Heard Museum and a fan. “That doesn’t always work out well for people.”

Cody conceptualizes her textiles as scrolls that can be “read from the bottom up or from the top down,” she said. “Think about where the attention-grabbing elements are and where you can place the viewer’s eyes.”

For non-weavers, one of the most extraordinary aspects of Navajo weaving is its largely spontaneous quality, completed with little sketching. “We graph it as a mental image. We recreate the textures of the natural world, the atmosphere and colors of the city in the form of textiles,” Cody said. “It’s slow and fluid, and everything is calculated down to the individual string.” The large-scale weavings take more than six months to complete.

Her mother often comes to help, following her daughter’s lead as she lines up the warp threads on the floor. This studio is definitely a family affair, with the looms made by his brother Kevin and the platforms made by his partners Giovanni and MacDonald and Sanchez.

The couple are now parents to a 3-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Aniwiahi (meaning “judge” in Navajo), and a 10-month-old son, Navaahi (Navajo meaning “warrior”). Cody plans to teach them how to weave, like her mother did, and hopes to make it a second habit, but is unsure whether to pursue it further. I plan to let the children decide as well.

She recently turned her love of “giant pixels” into digitized jacquard fabrics that were coded and sent to production looms in Belgium. This made it possible to adapt previous motifs and access colors and shapes that were not normally possible. traditional loom.

Among other motifs, Cody revived culturally significant motifs such as the “swirled log,” a symbol of Diné origins that was mistaken for the Nazi swastika and disappeared after World War II. . “To move forward as Indigenous artists, we need to reclaim our stories and honor our authentic selves in the work we create,” she said.

She continues to pass on her knowledge. In Los Angeles, she teaches Cody to elementary school students in under-resourced neighborhoods through an organization called Wide She Rainbow. She also works with the Autry Museum of the American West to host summer workshops for local Diné weavers. “A big part of Native American culture is reciprocity,” says associate curator Amanda Wixson (Chickasaw Nation). “Melissa has it in her bones.”

Recently in Long Beach, Cody, whose dark hair cascaded down the length of his spine, steered the weft of a string of jubilation. Her thoughts come to mind of her grandmother, who continues her experiments and remains a student of her art. “It is such an honor to have the ancient knowledge that my ancestors craved come to my fingertips,” she said. She says, “I feel like I breathe life into textiles, and vice versa; textiles give me life.”

Melissa Cody: Webbed Sky

Until September 9th at MoMA PS1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, Queens. (718) 784-2086, momaps1.org.