<\/div><\/div>”],”filter”:{“nextExceptions”:”img, blockquote, div”,”nextContainsExceptions”:”img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”},”renderIntial”:true,”wordCount”:350}”>

Sure, our national parks protect stunning landscapes that are the backdrop to countless fond memories for families and adventurers alike. But these parks have also been the scene of baffling crimes and strange scenarios, from gangster-owned moonshine operations to unexplained disappearances.

There are an estimated 330 deaths per year in our parks, according to the National Park Service. Most of those are accidental—drowning is the number-one cause—but the odd murder does occur.

People occasionally just seem to vanish. The Park Service even maintains a website with information about cold cases of people who went missing or were killed on park property, with clues or remains sometimes found but what happened still unknown. The oldest case on the site—the murder of a 10-year-old boy whose remains were found in Rocky Mountain National Park—has been open for 65 years. (If you have information about any of these, you can submit it through the site.)

I’ve compiled some of the most puzzling unsolved mysteries in our national park system.

A Severed Hand in Yosemite National Park, California

A woman walks along Glacier Point Road, Yosemite, with Half Dome in the background. (Photo: Artur Debat/Getty)

A woman walks along Glacier Point Road, Yosemite, with Half Dome in the background. (Photo: Artur Debat/Getty)

Yosemite National Park: Steep granite. Tall waterfalls. Traffic jams in the valley—and a severed hand found in a scenic meadow. In 1983, a family was exploring Summit Meadow off Glacier Road when one of the children discovered a severed hand and forearm. In spite of consistent searches from investigators, no other body parts were found, and authorities were unable to identify the victim or make progress on the case. In 1988, a skull was found across the street from the site, but the Park Service still couldn’t attach a name to the victim.

Summit Meadow, a sub-alpine area in Yosemite National Park, where the hand was found (Photo: NPS Photo)

Summit Meadow, a sub-alpine area in Yosemite National Park, where the hand was found (Photo: NPS Photo)

It wasn’t until 2022 that the Park Service, using a DNA profile from the remains, named the victim: Patricia Hicks, a woman linked to a local cult leader who allegedly used LSD to weaken and disorient sexual victims. The man had been convicted of assaulting women in the 1980s, but disappeared before he was incarcerated.

But according to a 2022 report by the San Francisco Gate and a 2022 episode of the ABC News show Wild Crime, investigators think the cult connection was incidental and that Hicks was actually killed by the notorious serial murderer Henry Lee Lucas, who confessed to hundreds of slayings across the nation. Lucas, at the time of his arrest, revealed details about the Summit Meadow crime scene that had not been released in the media.

Still, the details that Lucas gave regarding the incident and victim were deemed circumstantial, so the murder remains unsolved. Lucas died in prison in 2001, and the question of who was behind the murder of Patricia Hicks may never be solved.

The Newlyweds Who Disappeared in Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona

Friends watch from shore as a kayaker enters Lava Rapids. (Photo: Nyima Ming)

Friends watch from shore as a kayaker enters Lava Rapids. (Photo: Nyima Ming)

The Grand Canyon might be best known for its 5,000-foot walls, but the rapids at the bottom of that gorge are huge as well. The Green River and Colorado River descend for more than 270 miles in a torrent of class IV and V whitewater, with multiple massive waves and many boulders to maneuver around. Native Americans likely traveled the Canyon for hundreds of years, but the first European American documented as navigating it was John Wesley Powell, in 1869. Since then, roughly 100 people have drowned in the rapids.

Arguably the most famous and mysterious drowning or incident happened in 1928, when the newlyweds Glen and Bessie Hyde attempted to paddle the Grand Canyon on their honeymoon. They were in a boat that Glen had built, attempting a speed-record paddle through the canyon that would also have made Bessie the first woman to run it. (Rubber rafts wouldn’t become common until after WWII.) The Hydes were last seen on November 18, and their boat was found intact with all of their supplies a month later, on December 19. The boat was in perfect condition, with all of the contents, including Bessie’s diary, intact.

Search parties scoured the canyon, but their bodies were never found. It’s possible (and probable) that the couple was washed out of the boat during one of the rapids, and the vessel continued downstream without them. But Glen and Bessie were both experienced rafters.

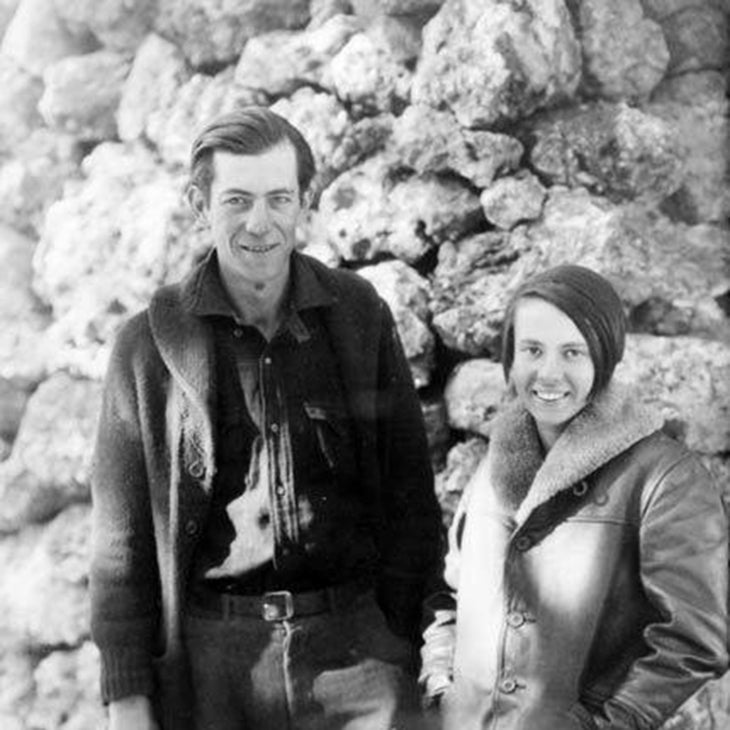

Glen and Bessie Hyde, November 17, 1928. Emery Kolb, an experienced Grand Canyon boater and explorer, took this photo of the Hydes on the Colorado River. He and his brother Ellsworth then joined the search for the two, finding only their boat. (Photo: Emery Kolb/ NAU.PH.568.4035, Colorado Plateau Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University)

Glen and Bessie Hyde, November 17, 1928. Emery Kolb, an experienced Grand Canyon boater and explorer, took this photo of the Hydes on the Colorado River. He and his brother Ellsworth then joined the search for the two, finding only their boat. (Photo: Emery Kolb/ NAU.PH.568.4035, Colorado Plateau Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University)

A popular theory has emerged over the years that Bessie murdered her new husband somewhere deep in the canyon. Another river runner, Emery Kolb, encountered the couple deep in the canyon and noted Bessie’s hesitance to continue the journey, and that they didn’t have life jackets.

In 1971, a woman named Elizabeth Cutler claimed to be Bessie Hyde, alleging that she stabbed her husband during a fight and had been living a different life ever since. Cutler eventually denied the claim, and it was later rumored that the pioneering river runner Georgie Clark, the first woman to own a commercial rafting business in the Grand Canyon, was actually Bessie Hyde.

After Clark died in 1992, the Hydes’ marriage license was found in her home, as well as a birth certificate identifying Clark as Bessie DeRoss, according to an account by North Arizona University. DeRoss was her birth name; why she changed her first name to Georgie is unknown. Georgie Clark was married twice, and had a daughter who died in a bicycle accident. We don’t have enough info to say Clark was the Bessie who disappeared in the Grand Canyon, and some historians have discounted the idea.

A Lost City in Everglades National Park, Florida

A misty landscape filled with spider webs at sunrise in Everglades National Park (Photo: Troy Harrison/Getty)

A misty landscape filled with spider webs at sunrise in Everglades National Park (Photo: Troy Harrison/Getty)

Everglades National Park is a large, jungle-like expanse of mostly water covering 1.5 million acres in Southern Florida. It’s also mysterious as hell, the site of more than 175 unsolved murder cases since 1965. Blame the remote nature of the park and its large population of man-eating beasts like alligators and bull sharks; a section of U.S. 41 running through the park, known as Alligator Alley, is a notorious place for murderers to dump bodies.

There are even theories of supernatural shenanigans. In 1945, a group of five Navy bombers took off from Fort Lauderdale on a routine two-hour training flight off the coast of Florida, but the leader of the crew radioed back to the control tower that they were lost. After several increasingly frantic communications, contact ceased entirely. A rescue air ship released to search for the bomber also disappeared.

These missing planes spawned the legend of the Bermuda Triangle, where many ships and planes have disappeared without explanation and which touches a corner of the Everglades. The planes have never been found, but one theory is that the bombers were well off course and crashed in the Everglades.

My favorite Everglades mystery, though, concerns a three-acre island in a remote section of the park south of Alligator Alley known as “The Lost City” that at various times throughout history has reportedly been a Seminole settlement, a Confederate soldier hideout, and a moonshine operation. The island doesn’t appear on any maps, and no roads or known trails lead to it. But according to an article published in the Orlando Sentinel, it is registered as an archeological site in the Florida State Archives and has been studied by state archeologists and wildlife officers, who uncovered ruins of wooden shacks, a canoe, Native artifacts and a large iron kettle, the type often used to distill moonshine out of sugar cane.

Some artifacts were hundreds of years old, but most came from the Prohibition era, when the island was likely used as the hub of a bootlegging operation. Historians aren’t sure why the original Seminole residents abandoned the settlement. As for the Confederate soldiers, who were supposedly hiding out after stealing Union gold, archeologists believe they were killed by Native Americans for trespassing on sacred ground.

The most recent legend surrounding the island has to do with Al Capone, who reportedly owned a speakeasy in a nearby town during Prohibition and may have run a moonshining operation on the island. Since both the speakeasy and the still were illegal operations, there’s no paper trail linking the gangster to The Lost City, so we may never know whether this part of his famous tale is true.

Missing Tourists in Death Valley National Park, California

Butte Valley, Death Valley National Park (Photo: W.Sloan/NPS Photo)

Butte Valley, Death Valley National Park (Photo: W.Sloan/NPS Photo)

Death Valley National Park is a notoriously inhospitable landscape. It’s known as the hottest place on earth, with the world-record highest air temperature of 134 degrees recorded at Furnace Creek on July 10, 1913. The desert, which sits in a basin almost 300 feet below sea level, gets an average of just two inches of rain a year, and when precipitation does come, flash floods are common.

Obviously, summer is one of the most dangerous times to visit the hottest place on earth, which might help explain what happened to four German tourists who disappeared inside the park in July 1996. The visitors, 34-year-old Egbert Rimkus and his 11-year-old son, and Cornelia Meyer, 27, and her 4-year-old son, were in the U.S. exploring California and the Southwest for a month. They rented a minivan in Los Angeles and entered Death Valley on July 22, scheduled to fly back to Germany on July 27.

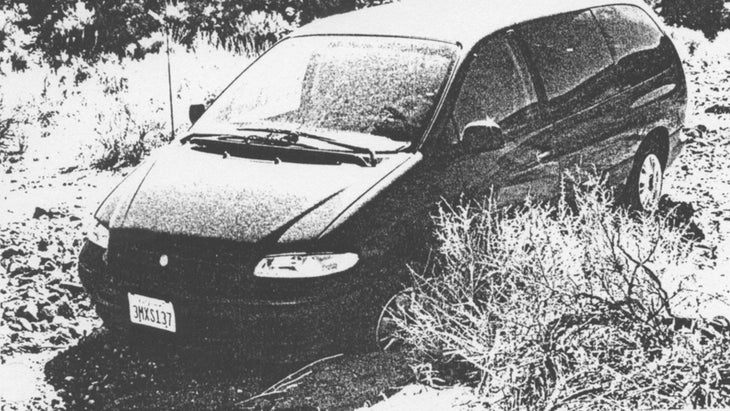

But they never made it out of the park. The minivan was found in October of that year by a ranger flying over the southern portion of the park looking for illegal drug labs. He spotted the vehicle in Anvil Canyon, a federally protected wilderness area of the park with no active roads. The van was stuck in the sand, the doors were locked, and three tires were flat.

The German tourists’ rental minivan was found stuck at Anvil Pass, Death Valley, by Ranger Dave Brenner on October 21, 1996. (Photo: Eric Inman, DVNP Report/NPS Photo)

The German tourists’ rental minivan was found stuck at Anvil Pass, Death Valley, by Ranger Dave Brenner on October 21, 1996. (Photo: Eric Inman, DVNP Report/NPS Photo)

Investigators linked the minivan to the Germans after tracking down the rental info and were able to trace their itinerary through receipts and wire transfers. After entering the desert on July 22, they camped in Hanaupah Canyon, when temperatures were hitting the mid 120s. Based on a logbook signed by the Germans, rangers believe the group was attempting to cross Mengle Pass—a rough, 4WD-only road at the end of Butte Valley—couldn’t make it, and tried to reroute through the roadless Anvil Canyon.

The badlands of Death Valley National Park seen from the classic viewpoint of Zabriskie Point (Photo: NPS Photo)

The badlands of Death Valley National Park seen from the classic viewpoint of Zabriskie Point (Photo: NPS Photo)

Rangers dispatched teams to search for the Germans after discovering the minivan, but were only able to find a single Bud Ice beer bottle located 1.7 miles east of the site. After four days and more than 250 people involved in the effort, the search was called off.

Getting lost in the desert and dying of heat stroke is the most plausible answer to the fate of the Germans, but the fact that they disappeared without a trace is puzzling. Some suspected foul play (possibly regarding illegal drug operations), and others suggested the Germans staged their disappearance to start a new life. Or could the Germans have seen something they weren’t supposed to at a nearby military institution? This area of the park was also near a ranch associated with Charles Manson and his cult.

Theories circled the lost Germans for more than a decade. It wasn’t until 13 years later that two avid hikers and search-and-rescue members from Riverside County, California, who had been researching the disappearance found the remains of the adult Germans in a remote and rugged portion of the park, four miles from the border of the China Lake Military Facility and eight miles from their minivan. More bones were found on subsequent searches, but there wasn’t enough DNA to connect the remains to the children.

In 2009, a search of the rugged area turned up various items and skeletal remains. Tom Mahood wrote in otherhand.org, “As I looked across the hillside and saw all the orange shirts methodically moving across it….I [thought] the Germans’ families would be touched to see all the interest in their missing relatives even after all these years.” Some of those on scene had been on the original search. (Photo: Tom Mahood )

In 2009, a search of the rugged area turned up various items and skeletal remains. Tom Mahood wrote in otherhand.org, “As I looked across the hillside and saw all the orange shirts methodically moving across it….I [thought] the Germans’ families would be touched to see all the interest in their missing relatives even after all these years.” Some of those on scene had been on the original search. (Photo: Tom Mahood )

Evidence seems to point towards the visitors making a series of fatal mistakes, like using outdated maps and traveling in the desert without sufficient emergency supplies, then attempting a shortcut (Mengle Pass) on unknown terrain. The fact that four people, including young children, were able to leave the van and hike for miles without leaving a trace, save for a single beer bottle, is still odd. In the end, so much time passed between the Germans going missing and the partial remains being found, that investigators will likely never have a complete picture.

A Child Disappears in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee and North Carolina

The dense greenery of Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Photo: Nathan Mullet/Unsplash)

The dense greenery of Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Photo: Nathan Mullet/Unsplash)

Great Smoky Mountains is probably best known as a drive-through park—a place where most people stick to the roads, established viewpoints, and short nature trails starting within a few feet of parking lots. But there are remote sections of the park, and the forest is dense, with a thick understory of rhododendron obscuring terrain beyond the trail. That’s the terrain that the Martin family was camping in when their six-year-old son, Dennis, disappeared in 1969.

Spence Field, where the Martins and their friends were camping. Trees have since grown up in the pasture. (Photo: Brian Stansberry Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons)

Spence Field, where the Martins and their friends were camping. Trees have since grown up in the pasture. (Photo: Brian Stansberry Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons)

Over Father’s Day weekend, the Martins and two other families camped out in Spence Field, a backcountry meadow of roughly five miles from the nearest road. Dennis, his older brother, and a few other boys wanted to play a prank on their parents, hiding in the bushes and jumping out to scare them. Dennis’s father saw his son step off the trail into the bushes—and it was the last time anyone ever saw him.

When the other boys jumped out of the bushes a few minutes later, Dennis was absent. The family searched for him for four hours before hiking to the nearest ranger station to alert authorities. A massive search commenced, with more than 1,000 people involved, but no sign of the missing child was found.

To this day, the search remains the largest ever deployed in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and it influenced the way in which national parks undertake modern searches. It’s now widely accepted that the sheer volume of inexperienced people looking for Dennis probably obscured any clues that professional search-and-rescue crews might have uncovered. Now, when a person goes missing inside a park, a few experienced trackers are deployed first. Only hours or days later are larger search parties engaged in the effort.

Sunset at Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Photo: Ivana Cajina/Unsplash)

Sunset at Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Photo: Ivana Cajina/Unsplash)

The FBI suspected no foul play in the case of Dennis Martin. A number of false reports initially gave hope for some closure for the Martin family, but none panned out. Early in the investigation, a witness reported hearing a child scream and seeing a strange man drive away in a white Chevy, but investigators ruled the incident unrelated because it was too far from the last place Dennis was seen. In the 1980s, a hiker looking to harvest ginseng illegally inside the park reported finding the skeleton of a child roughly 10 miles from Spence Field, but when rangers searched the area, they found nothing.

A Murder in Mount Rainier National Park, Washington

A forest in Mount Rainier National Park (Photo: Javaris Johnson/ Snipezart)

A forest in Mount Rainier National Park (Photo: Javaris Johnson/ Snipezart)

National parks rely heavily on seasonal employees, who generally occupy jobs during the busy, warm months, often living in employee housing. That was exactly what Sheila Kearns was doing in Mount Rainier National Park in 1996. Sheila Kearns, age 43, was hired to work in the park’s Paradise Inn in August, and by all accounts was so good at it that she was hired to stay on through the winter.

Employees at Mount Rainier mark the end of a season with a bonfire and party. The last time anyone saw Kearns was at one of those parties, on October 4, 1996, when she told a coworker how excited she was to stay on. Kearns was in the process of moving into her new employee housing unit over the next few days when she disappeared. On October 6, she didn’t show up to work. Her possessions were in her new room, but there was no sign of Kearns.

The Paradise Inn lodge in Mount Rainier National Park, Washington (Photo: Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket/Getty)

The Paradise Inn lodge in Mount Rainier National Park, Washington (Photo: Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket/Getty)

A three-day search in the park revealed nothing. As the Seattle Times wrote in 1997, “Park officials at first believed Kearns might have become lost on a trail but later said she might have been abducted.” Winters are rough in Mount Rainier, and within weeks of the search, snow set in. Seven months later, in May 1997, after the spring thaw, a volunteer who was setting up a navigation course for park rangers found skeletal remains at the community building in the old Longmire campground, about a mile from the inn. The remains were scattered around a 300-yard area.

Almost 40 years later, the question of who or what killed Kearns remains unanswered. At the time the FBI investigated possible suspects but to this day does not have a person of interest.

Graham Averill is Outside magazine’s national parks columnist. He’s easily spooked and admits that researching these mysteries made him think twice on multiple occasions recently when out in the woods on his own. But even after exploring these unfortunate events, he knows that the national parks and forests are arguably the safest places in the country.

Our now disquieted author in the woods (Photo: Graham Averill)

Our now disquieted author in the woods (Photo: Graham Averill)