I have written extensively about tourism trends.

Currently, some of the most popular tourist destinations in the world are Portugal, Dubai, Bali, etc. Every year, millions of travelers from all over the world flock to these places.

Each hotspot has its own tourism approach, which usually involves improving infrastructure, showcasing culture and nature, and offering unique sights to visitors (although sometimes it may be necessary to keep large numbers of tourists at bay to prevent over-tourism).

But has tourism always been like this?

For centuries, bold adventurers have slung a bag over their shoulder and set off toward the horizon, never knowing if they’ll ever return. They may not even be able to pinpoint on a map where their loved ones are headed.

But everyone was looking for something inspiring, something powerful and life-changing.

Today, the quest for something more remains an important part of the overall travel experience, and although most vacations now have far more of a recreational and relaxation component than they did in the past, the fundamental motivation for travel remains the same.

But what were those tourists doing back then? Can we really understand what motivated them to travel and explore? To find out, let’s go back to the early 1900s.

Here are three trends in U.S. tourism since the turn of the last century.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Niagara Falls, New York

View the waterfall from inside a barrel

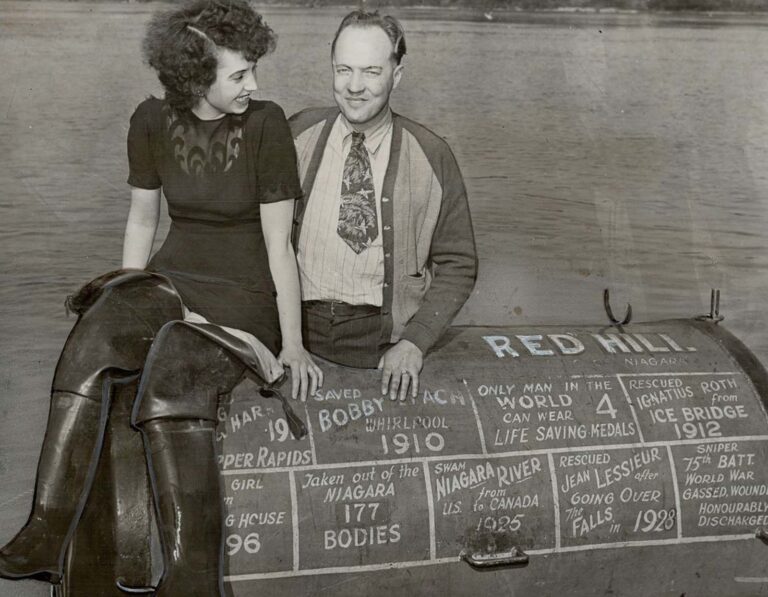

In 1901, 63-year-old teacher Annie Edson Taylor decided that simply admiring Niagara Falls wasn’t enough.

She had another idea: to build a very strong wooden barrel just big enough for her to fit in, and then she would squeeze herself into it, lock the wooden latch, and ride the barrel over Niagara Falls.

To rationalize his decision, Taylor first put his cat in a barrel and threw it over a waterfall. The cat survived, so Taylor took that as a green light.

Soon after, Taylor performed a wooden barrel stunt in front of a huge crowd, and she stumbled away largely unscathed, posing for photos with the daredevil cat.

Taylor’s incredibly daring (and perhaps insane) stunt attracted a lot of attention, and it soon became a trend for fearless tourists to traverse the falls in unique and terrifying ways.

Some, like Jean Lussier, have survived falls by climbing into giant rubber balls. In summer, the area attracts hundreds of thousands of tourists, most of whom just come to enjoy the views. By 1951, any form of descent of the falls was declared illegal.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Atlantic City, New Jersey

Summer holidays and street fairs

Fans of Boardwalk Empire need no introduction.

Long before Las Vegas appeared in the desert, America’s favorite summer resort was Atlantic City, New Jersey.

The original boardwalk was built in 1870 and ushered in a new era of Americana summer vacations.

After the boardwalk was completed, AC was transformed into a popular family summer destination: a combination of carnival, beach resort, and summer dream that attracted revelers from all over New England.

Soon the hotel grew to be huge, with hundreds of rooms that were fully booked for months from May through August.

Despite its focus on summer and sweet treats, AC had a bit of a criminal backstory (to say the least).

Much of the city’s construction was funded by organized crime syndicates, which were the subject of extensive federal investigations and involved big-name gangsters such as Al Capone and Charlie Luciano.

But the millions of people who flocked to Atlantic City’s sandy beaches had their eye on cutting-edge pleasures like ice cream, primitive roller coasters, and summer love. In other words, AC was the American Dream.

Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

St. Louis World’s Fair

Internationally renowned cultural figures

St. Louis may not have the greatest reputation in the United States today, but it was once one of the most populous and innovative cities in the country.

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Louisiana Purchase, the federal government and the city of St. Louis acquired the rights to host the World’s Fair.

For six months in 1904, St. Louis became a nonstop street fair, drawing nearly 20 million visitors from around the country and beyond. Performers and exhibitionists from more than 60 countries flocked to St. Louis to show off their latest moves and most beloved traditions, and share countless new delights.

As a global studies major and St. Louis native, I’m itching to point out the lesser known, more sinister legacies of the St. Louis World’s Fair.

(Ever heard of a guy named Ota Benga? Or the tradition of the veiled prophet of St. Louis? Folks… that’s some pretty dark stuff.)

Feel free to follow the little breadcrumbs I left behind if you like, but if not, let me conclude this article with some of the World’s Fair’s least controversial coups.

The fair popularized treats like ice cream cones and Dr. Pepper. It also put Scott Joplin on the map and paved the way for ragtime music. The fair even had an exhibit dedicated to geisha, who traveled all the way from Japan to showcase their refined traditions.