TBILISI, Georgia — In the ancient home of khachapuri cheese bread and the famous earthenware-fermented qvevri wine, Danny Licht is now serving up a national dish to rival it: falafel.

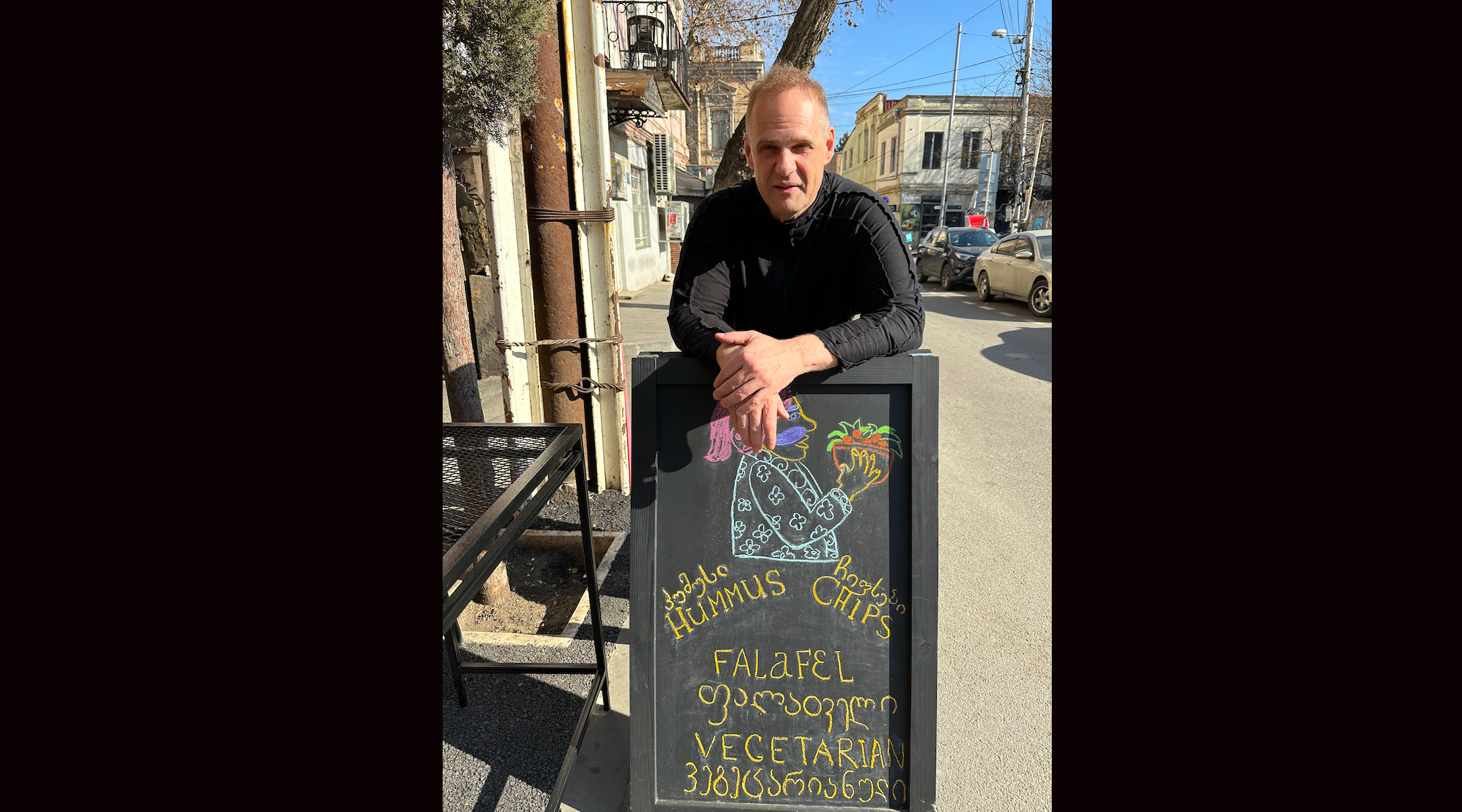

The Swiss-Israeli entrepreneur moved here from Jerusalem with his Russian-born wife, Rita, three years ago, and in January they opened Ashkara Falafel in the heart of Tbilisi’s tourist district.

“We wanted to offer something fresh, tasty and cheap — not a restaurant, but real street food,” said Licht, who sells a full falafel course with all the accompaniments for 19 lari (about $7).

Meanwhile, Rita, who earned her PhD in molecular genetics from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, runs a contemporary art gallery in the same building as her home.

“We don’t have family connections here, but we love the culture here and are passionate about the arts,” she said. “Our dream was to open a gallery and this is one of the places where we can do that.”

Danny Licht, a Swiss-Israeli new immigrant to Georgia, stands in front of his Ashkala Falafel shop on Lermontov Street in Tbilisi. (Larry Luxner via JTA.org)

Danny and Rita Licht are among about 200 Israelis who see Georgia, a former Soviet republic about a three-hour flight from Tel Aviv, as a new promised land. Frustrated by Israel’s high prices, toxic politics and deteriorating security situation, they decided to settle permanently in the mountainous country, landlocked in the Caucasus Mountains.

They may have left the divided country for other countries. In the past two months, Georgia has seen large-scale anti-government protests against a new law modeled on a Russian one that requires organizations that get more than 20 percent of their funding from abroad to register as “foreign agents.”

Critics say the law is aimed at stifling dissent and moving the country closer to Moscow and away from the European Union. Polls show 80% of Georgians want their country to join the bloc, and protesters have vowed not to back down until the law, which they say reeks of Putin-like repression, is repealed.

It remains to be seen whether the new law and backlash will affect Israel’s long-strong tourism industry. According to government statistics, 217,065 Israelis visited Georgia last year, making it the fourth-largest source of foreign tourists after Russia, Turkey and Armenia. But Israelis stay longer and spend an average of 3,782 lari (about $1,400) per visit, far more than any other group. It’s not uncommon to hear Hebrew on the streets, and one of Tbilisi’s tourist attractions is the Museum of the History of Georgian Jews, which documents 2,600 years of Jewish life in the country.

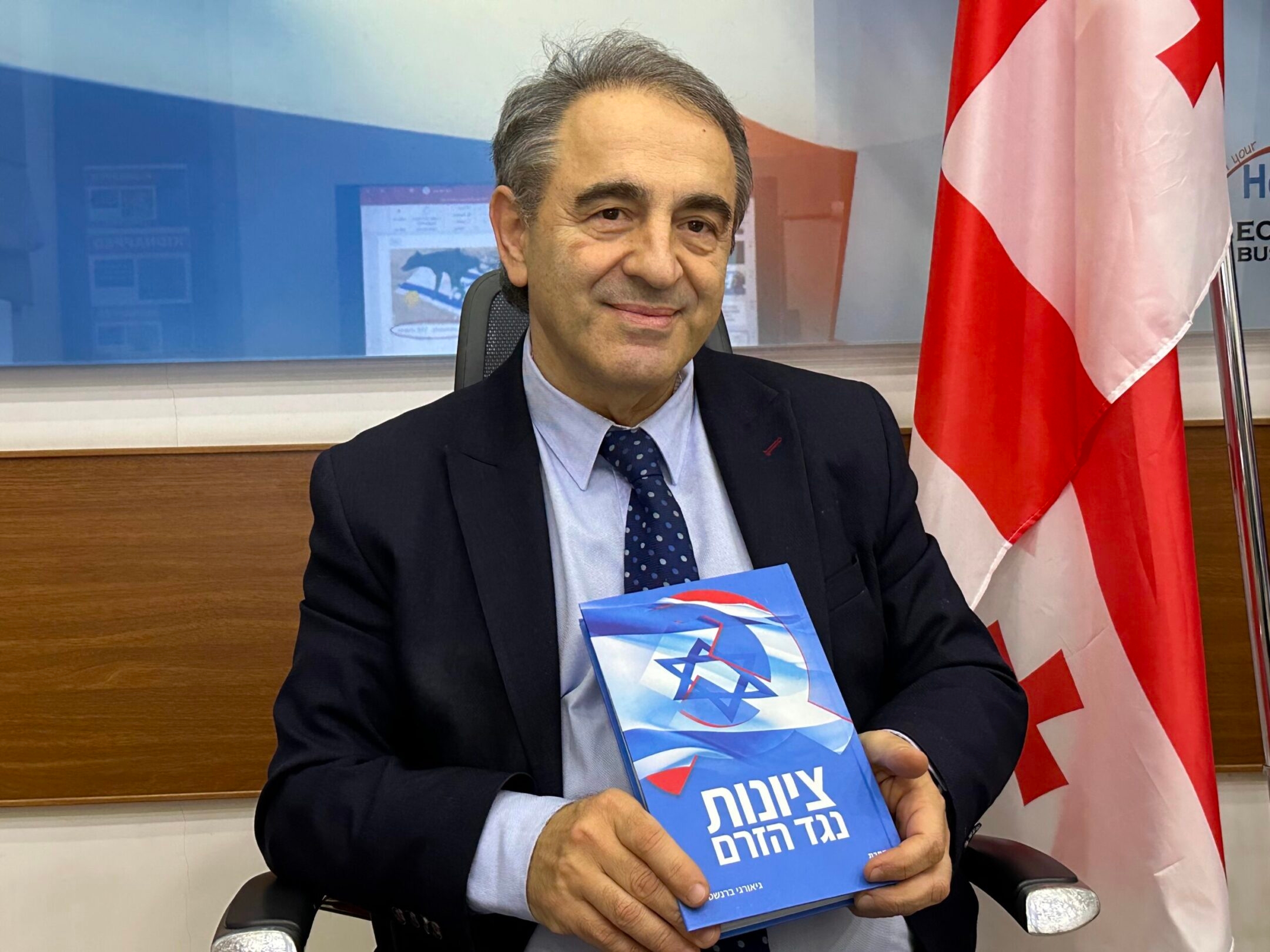

Itzik Moshe, founder of Israel House and the Israel-Georgia Chamber of Commerce, said total Israeli investment in tourism, finance, agriculture and healthcare has already reached about $500 million.

“Georgia is a small country, but it is one of Israel’s best friends in the world,” said Moshe, who became the first Israeli to head the Jewish Agency in the former Soviet Union in 1990. “We are two ancient peoples with a difficult history and a common fate. According to Georgian history, it was the Jews who helped prepare them to embrace Christianity.”

The Georgian Jewish Museum is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Tbilisi, Georgia. (Larry Luxner via JTA.org)

In fact, legend has it that a Georgian Jew named Elias obtained Jesus Christ’s clothing from Roman soldiers at Golgotha after the crucifixion and brought it back from Jerusalem.

Before October 7, four or five airlines offered direct flights between Tel Aviv and Tbilisi, sometimes even twice a day by the same airline. Today, El Al and Israel Airlines still fly daily on the route. Posters of Israelis kidnapped by Hamas and held captive in Gaza can be seen on billboards and on the sides of buses in Tbilisi.

Despite the warm feelings, not everyone here loves Jews or Israel.

In November 2022, al-Qaeda-linked Pakistani operatives from the Quds Force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps attempted a street assassination in front of the Israeli flag above Moshe’s office. Fortunately, the plot was discovered by local security authorities, who arrested several suspects, including two Georgian-Iranian dual nationals.

Moshe, who remains on high alert, said he expects a record 250,000 Israelis to be in Georgia in 2024. In November, his organization will host a business conference in Tbilisi to mark 35 years of commercial ties between the two countries.

One of Georgia’s most prominent Jews, Itzik Moshe, is the founder of Israel House and president of the Israel-Georgia Chamber of Commerce. (Larry Luxner, via JTA.org)

In fact, many Israelis buy timeshares in the Black Sea resort of Batumi, and the country is considered a top destination for skiing, hiking, and food- and wine-focused travel. Unique to Georgia is its ancient 33-letter alphabet that is nearly 1,500 years old, and the hauntingly beautiful chants sung in three-part polyphony without instruments during daily and weekly services in Georgian Orthodox Churches.

“I’ve never met an Israeli tourist who didn’t want to come back here,” Moshe said. Georgia’s Jewish population is estimated at between 500 and 1,000. The Great Synagogue in Tbilisi serves a mostly elderly community. In addition to Israeli Jews who have immigrated to Georgia, 1,500 Israeli Arabs, mostly Christians from Nazareth and elsewhere, are studying medicine here.

Similarly, there are about 120,000 Georgian Jews living in Israel. Known in Hebrew as Gurjinim, they originally settled in Ashdod, Beersheba, Ashkelon and Haifa but have since spread across the country, with some having returned.

Ilana Slutsky, a native of Orenburg in southern Russia who grew up in Haifa and worked as an architect for many years, said her company had signed a contract with a cardiovascular center in Georgia that required her to travel there from Israel every 10 days for four years.

Slutsky eventually moved to Tbilisi, where she founded an interior design, real estate and architecture consulting firm a few years ago. Her Georgian husband, Ted, is an artist, and she is currently restoring an apartment building built in 1872.

Froml

From left: Gallery owner Rita Licht, Israel-Georgia Chamber of Commerce President Itzik Moshe, Ashkala Falafel owner Daniel Licht, architect Ilana Slutsky and jewelry designer Mikhail Gilitinsky enjoy a Shabbat afternoon with fellow Israelis at Licht’s house in Tbilisi. (Larry Luxner via JTA.org)

The only time she felt uncomfortable, she recalls, was when she saw a recent Instagram post by Mutant Radio Tbilisi asking for donations for Palestinian children displaced by the war in Gaza.

“My heart goes out to all the victims of the war, but I know that this money will go directly to Hamas,” said Slutsky, who speaks Georgian in addition to English, Hebrew and his native Russian. “For me, it was disappointing, especially considering what happened at the Nova music festival. To be honest, I was shocked.”

Russians are not particularly welcome in Georgia, despite the large amount of money they have invested and the government imitating their home country. Georgia seems to be rife with Ukrainian flags, a sign of support for the former Soviet republic. This is a relic from the 2008 Russia-Georgia war, which began when pro-Russian separatists from the breakaway republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia attacked Georgia in violation of a 1992 ceasefire. The fighting ended after 16 days, with Russia taking control of a fifth of Georgia’s territory.

The retaining wall opposite Danny Licht’s falafel shop is covered in anti-Russian obscenities, and some nightclubs require patrons to sign statements in support of Ukraine (and Georgia, another victim of Putin’s aggression) before entering.

“When the Russia-Ukraine war started, rents in Georgia were 30 to 40 percent cheaper than they are now,” Licht says. “But then apartment prices doubled or even tripled. A lot of Russians fled to Georgia, and the market went into chaos. They couldn’t use their credit cards in Russia. Then last September, Georgian housing prices crashed.” [military] “They were mobilized. They didn’t come because they were against the war, they came because they didn’t want to be killed.”

Licht added: “Prices peaked about six months ago and are now falling. But 20 percent of the country is still occupied by Russia and Georgians are very suspicious of Russia.”

A woman waves a Georgian flag during a protest against the “foreign influence” law outside the parliament building in central Tbilisi on May 28. (Giorgi Arjevanidze/AFP via Getty Images via JTA.org)

Yaron Shmelkin, 39, has been living in Georgia for nearly two years. Originally from the Russian-occupied city of Luhansk in eastern Ukraine, he is married to Georgian fashion designer Anuk Yosebashvili. In 2017, the jewelry designer, who specializes in Jewish art, took a jeep tour with his wife and parents-in-law through the mountainous republic, which is three times the size of Israel but has less than half its population.

“A week later, I said, ‘Let’s move here,'” he recalls. “We’re very happy in Georgia.”

Such is the case with Mikhail Gilitinsky, 40, an Orthodox Jew from the Russian city of Tula, who lived in various parts of Israel (Kibbutz Balam, Jerusalem and Ramat Gan) before coming to Georgia five years ago with his Moscow-born wife Miriam. Both had previously come to Georgia on holiday.

Neither Mikhail nor Miriam Gilitinsky speak Georgian and use English to communicate with locals because, as Mikhail says, “I feel uncomfortable speaking Russian.”

But Gilichinsky built a small hotel that his wife runs as an Airbnb, and their children, ages 10 and 7, attend a local Chabad religious school.

“I’m a jewelry designer, so I can work from anywhere,” he says. “We love Israel, but it’s hard financially. You have to work all day, every day. That’s why we came here.”