Really support

Independent journalism

Click here for detailsClose

Our mission is to provide unbiased, fact-based journalism that holds power accountable and exposes the truth.

Every donation counts, whether it’s $5 or $50.

Support us to deliver journalism without purpose.

In Sicily, lakes are drying up and fields are baking in the heat, but water still springs up in abundance for tourists.

The Italian island has had almost no rain for a year, but the fountains in Agrigento’s famous archaeological park are still flowing and the hotel pools lining the island are full to capacity.

Like many Mediterranean islands, Sicilians are used to long periods without rain, but human-made climate change has made the weather more erratic and droughts longer and more frequent. Islanders are surviving as they have for decades: storing as much water as they can in cisterns and transporting it in tankers. Tourists are doing so well that they don’t even notice the difference. But this year the drought has worsened, putting residents at greater risk, even though hotels and tourist sites still have water flowing.

Resilient in dry years

The drought is so severe that local water authorities are severely rationing water to help nearly a million residents get through the summer, who only use it for two to four hours a week, and on Friday, the first Italian Navy tanker arrived to deliver 12 million liters (3.2 million gallons) of water to the hardest-hit residents.

But Agrigento’s residents are among Italy’s most drought-resistant, and even under rationing they have kept their businesses, hotels, bed and breakfasts and homes running without skipping showers, neglecting gardens or closing swimming pools.

“Nobody can cope with water shortages better than the people of southern Sicily,” said Salvatore Cocina, head of the local civil defense agency, which has the difficult task of regulating what little water remains on the island.

Water shortages are nothing new in southern Sicily, where the terrain doesn’t hold much water and water pipes are leaky, making the region prone to droughts, especially in the summer.

Most residents have personal tanks that hold at least 1,000 liters (264 gallons) of water: large plastic tanks dot the city’s rooftops, with an equal number in yards and basements.

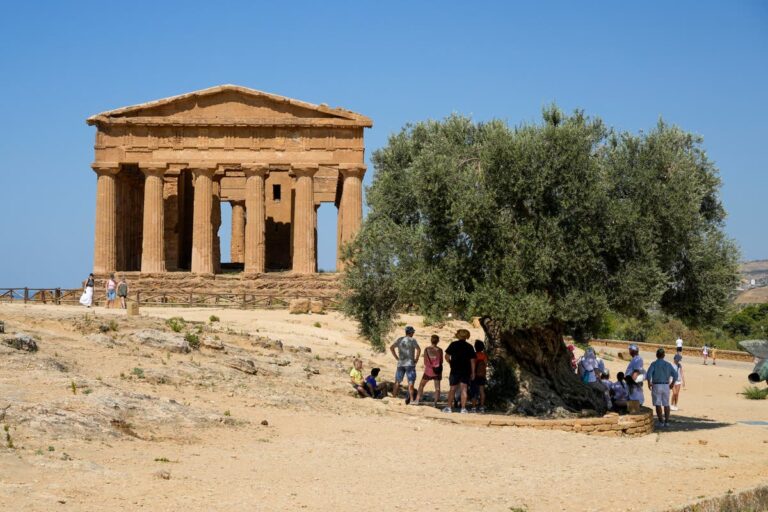

Despite a water shortage crisis, tourists are flocking to southern Sicily’s beautiful beaches and queuing to admire the ruins of an ancient Greek colony.

“We didn’t have any water problems,” New Zealand tourist Ian Topp said, sweating in the hot sun during a visit to the 2,500-year-old Temple of Concord, but added that “we were told to conserve water in case there were shortages.”

“In my experience, drought is not a problem,” said Gianluca, an Italian tourist from Lodi, who declined to give his surname. “The hotel I was staying in told me they had their own water reservoir.”

The Valley of the Temples, which its director says attracted more than one million tourists last year, has not suffered from water shortages because it is a priority for protection.

“We have water 24 hours a day, 365 days a year,” explained Director Roberto Sciaratta, “archaeologists are working, the valley is open at night, theatres are being performed, there are no problems with the water supply.”

Meanwhile, water-scarce residents’ strategies have worked reasonably well so far, but they face an extremely difficult situation.

According to the regional civil defense, 2024 is the wettest year in more than 20 years. Lake Fanaco, which supplies water to the province of Agrigento, used to collect up to 18 million cubic metres of water during an average rainy season that usually lasts from September to April. But by April the lake’s water level was already below 2 million cubic metres and it is now almost completely dry.

In May, the government declared a state of emergency over the drought and allocated 20 million euros ($21.7 million) to buy water tankers and dig new wells.

And temperatures in southern Sicily are now 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the 1991-2020 average, according to the Climate Shift Index, meaning water is evaporating more quickly.

“If there is no rain in September, we will have to start pumping important reserves and lakes as well as wells and aquifers will fall below critical levels,” Kosina said.

Lack of solutions

Salvatore Di Maria’s mobile phone rarely stops ringing. He is the driver and owner of the region’s main water tanker fleet.

On a recent hot day at a public water station, Di Maria pulled out his cellphone as he helped yet another customer refill his shiny blue tank.

“We need 12,000 liters (3,170 gallons) of water,” said a voice on the other end of the phone from the tourist site.

“There is a waiting list of 10 to 15 days,” Di Maria replied.

Everyone wants water from him. Everyone wants to make sure it never runs out. Everyone wants the tanks to be full. And a tanker is the best way to get that precious water directly to the residents without any leaks.

Dozens of tanker drivers are speeding down winding roads to deliver water to priority areas identified by the local water company, AICA, including the sick and elderly, hospitals, hotels and other key businesses.

“The drought emergency was a wake-up call,” explained AICA president Settimio Cantone. “Our water systems are leaking 50 to 60 percent of the water.”

“We are now using emergency funds to dig new wells, repair our entire water system and get our desalination plants up and running again, which will help our state become more self-reliant,” he said.

“Sicily is very vulnerable because of leaky water pipes and an old and insufficient infrastructure – it’s not just a climate problem,” said Giulio Boccaletti, scientific director at the European-Mediterranean Climate Change Centre.

Between water truck visits, some Agrigento residents frequent the town’s only remaining public water fountain to fill up jerry cans on their way home.

Nuccio Navarra is one of those residents, who fills his jerry can with water from the Bonamorone fountain two or three times a day: “My house gets water every 15 days, but the pressure is very low and the people living upstairs cannot fill their tanks,” he says.

Climate scientist Boccaletti worries about the future, but notes that some of his concerns could be offset by investing in water infrastructure and agricultural and engineering adaptations, as AICA hopes to do.

The Mediterranean region “will experience increased temperatures, reduced rainfall and continued sea-level rise over the coming decades,” according to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which labelled the region a “climate change hotspot” due to the vulnerability of human communities and ecosystems.

“What was once abnormal has become the new normal,” Boccaletti said.

___

Associated Press climate and environment coverage receives financial support from several private foundations. The AP is solely responsible for all content. See AP’s philanthropic engagement criteria, a list of supporters and funded areas of coverage on AP.org.