Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics of the main variables are given in Table 2. Panel A presents the information about cities that issued digital travel vouchers, while Panel B presents information for cities that did not issue vouchers during the same sample period. Among all the cities in the sample, 69 issued vouchers, constituting approximately one-fifth of the total cities. The average influx of tourists into cities in Panel A is much higher than that in Panel B. On average, the difference between issuing cities and non-issuing cities is 0.128, indicating the potential impact of digital travel vouchers in attracting tourists and boosting local tourism.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics.

In Table 2, it is shown that the average annual GDP of cities in Panel A is higher than that of cities in Panel B. These findings jointly suggest that governments in economically advantaged areas are more likely to support the tourism industry through issuing digital travel vouchers. The last row shows that, on average, cities issuing vouchers have a higher number of confirmed COVID cases compared to their counterparts in Panel B. This might imply that cities severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic are more inclined to issue digital vouchers to revive their tourism sector.

The correlation matrix of the main variables is presented in Table 3 below. Clearly, some variables exhibit reasonably high correlations. For example, the values of issuance, publicity, and availability are highly correlated, which is not entirely surprising. It is often the case that a large volume of issuance attracts more attention and involves more resources from businesses. These two variables will be used for robustness analysis. To address concerns regarding multicollinearity, we conduct typical VIF tests, which reveal no significant issues of collinearity in the main model. The results are not reported here due to space constraints but will be available upon request.

Table 3 Correlation matrix for main variables.

Baseline model results: the impacts of digital travel vouchers

Following the discussions above, we first investigate whether digital travel vouchers issuance and the associated values can affect tourist inflows. The results are reported in Table 4. This table presents the findings using six different specifications and sampling frames. In all models, we control for monthly and provincial fixed-effects. Along with the full sample analysis, we have included three sub-sample regression results: one excluding extreme months, another excluding major public holidays, and a third considering only the cities that issued digital travel vouchers throughout the entire sample period.

Table 4 The impacts of digital travel vouchers on tourist inflows.

Based on the results presented in Table 4, clear evidence emerges indicating that issuing digital travel vouchers can significantly increase tourist inflows. Controlling for city-specific factors, the effect of issuing digital travel vouchers is 0.078 according to the DID regression results, and this result is statistically significant at the 5% level of significance. The issuance value also shows significant results (models (1) and (2)). These impacts are generally consistent when different samples are considered. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is verified.

Regarding the control variables, the results generally align with intuition and economic logic. Larger cities, in terms of population, tend to attract more tourists, as do economically more developed cities. This trend extends to factors such as infrastructure and urban environment. Notably, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases exerts a significant and negative impact on tourist inflows, indicating that a more severe wave of the pandemic reduces tourist visits and accelerates the deterioration of local tourism. It is interesting to observe that the contribution of high-speed railways is not significant. This finding is consistent with Gao et al.’s (2019) findings, suggesting that the effects of high-speed rail on tourism are not always positive, especially when factors such as population and other developmental considerations are controlled.

Extended models: factors that determine the vouchers’ effectiveness

While the above analysis shows the positive and significant impact of digital travel vouchers on promoting local tourism, our interest lies in the subsequent question of how to enhance the effectiveness of their issuance. To explore this, we extend the previous model (Eq. (2)) by incorporating issuing characteristics and assess the effects through interaction terms. The results are presented in Table 5. It should be noted that the DID model only considers the first issuance as the treatment; therefore, these additional characteristics could not be effectively utilized. We thus focus on the ‘value’ for the following study.

Table 5 Results of the extended models.

In this section, three factors are considered. First, we demonstrate the significance of the choice of issuing platforms. Selecting larger platforms can significantly enhance the effects of issuance and increase the value effect. Larger platforms are generally more user-friendly and credible. According to the TPB model, the creditability of larger issuing platforms should boost behavioral intentions, thereby increasing the likelihood of visitors choosing issuing cities (Cabiddu et al. 2013). The results in model (1) of Table 5 confirm this hypothesis. Digital travel vouchers issued on larger platforms are generally associated with higher tourist inflows and can also amplify the value effect, as indicated by the significant interaction terms.

The second factor considered in the extended model is frequency; that is, how many times a city issues digital travel vouchers during the studied period. Repeated issuance of vouchers can reinforce consumers’ behavioral beliefs, thereby increasing the likelihood of visits. From the regression results in Column (2) of Table 5, the coefficient on frequency is positive and significant, confirming the projection that repeated issuance of digital travel vouchers can effectively attract more tourists. An intriguing aspect is the negative interaction terms with value. This result suggests that issuing frequency can diminish the value effect. In other words, issuing digital travel vouchers in smaller values many times could generate a stronger attraction for tourists.

To highlight the digital nature of the vouchers studied in this paper, we also consider regional internet penetration as a proxy for digital inclusiveness. Following the discussion in Section 3, we would expect to observe stronger effects of issuing digital travel vouchers in cities with higher levels of digital inclusiveness. Better digital development in a city makes the digital travel vouchers easier to use. Moreover, within the TPB framework, this could also be interpreted as stronger normative beliefs, leading to higher behavioral intention (Bosnjak et al. 2020). From Column (3), although internet penetration is statistically insignificant in the regression, the interaction term is positive and significant at the 5% level of significance. To summarize, H2 holds.

City-level heterogeneity analysis

This section examines whether cross-city heterogeneities, namely, city reputation and the level of a city’s digital financial inclusion, affect the effectiveness of digital travel vouchers. First, a dummy variable is created (Reputation), taking value 1 for well-known tourist cities and 0 otherwise according to the list of National Comprehensive Tourism Demonstration Zones released by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of China. For digital finance development, we adopt the sub-indices—the coverage breadth and usage depth of digital finance—released by the Digital Finance Research Center of Peking University. The breadth of digital finance is mainly reflected in the coverage of digital financial accounts, payment business, and money fund business. The depth of digital finance is assessed based on the credit business, insurance business, investment business, etc.

Interaction terms are used in the regressions to reflect heterogenous effects, and the results are reported in Table 6. In column (1), although the coefficient on city reputation is positive, but it is not statistically significant, meaning well-known cities do not have advantage in attracting tourists. Due to the influence of the pandemic, people are less enthusiastic about travelling, applying to all type of cities (Jiang et al. 2022). The interaction term between city reputation and voucher issuance value is however, positive and significant at 10% level, implying that the popularity of voucher campaigns can be amplified by city reputation.

Table 6 Heterogeneity analysis (PPML model).

Columns (2) and (3) in Table 6 report the influences of city-level digital financial inclusion. Both the breadth of digital finance coverage and its interaction term with the value of vouchers have positive impacts on tourist inflows, and they are significant at the 1% level of significance. As better digital finance coverage provides faster and easier access to digital financial products and services, it creates great convenience for customers using online travelling tools, meanwhile boosting the chance of using digital travel vouchers. In contrast, the depth of digital finance usage makes an insignificant contribution, though its interaction with value is positive and statistically significant.

These results emphasize the importance of the to-customer dimension of digital finance, rather than the to-business dimension, in promoting local tourism. Consumers tend to prefer cities with wide coverage of digital finance applications, while the extent of application by business-end users is not a major concern for them. We also notice that both interaction terms exert significant and positive impacts on tourist inflows at the 1% level of significance. This indicates that the effects of vouchers can be enhanced by both the breadth and depth of urban digital finance, and vice versa. Cities with developed digital finance technology are more experienced in and capable of advocating and facilitating the utilization of vouchers through diverse channels, thus making their vouchers more convenient, appealing, and effective.

Spatial spillover effect of digital travel vouchers

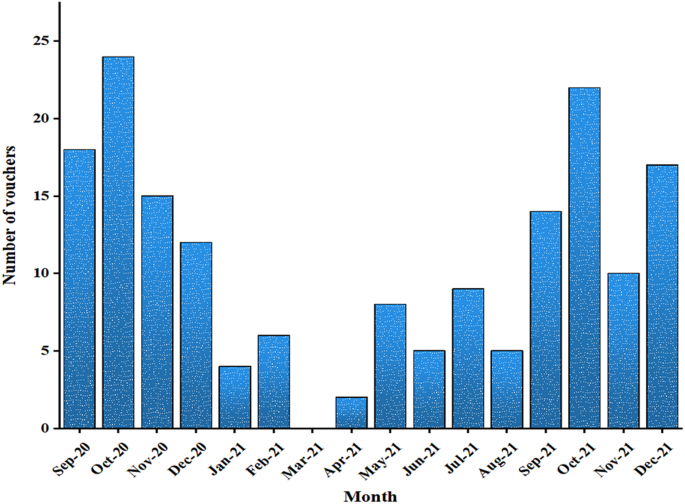

In this section, we investigate the potential spatial spillover effect of digital travel vouchers from the perspective of city clusters. The results of the Moran index test are presented in Table 7. The Moran index of tourist inflows for each month during the sample period is positive at the 1% level of significance. These findings strongly reject the null hypothesis of no spatial autocorrelation, indicating that our tourist inflow data exhibit a pattern of spatial autocorrelation and thus meet the prerequisite for spatial econometric analysis.

Table 7 Results of the Moran’s I test: September 2020 to December 2021.

Then, we apply the Spatial Durbin Model based on the spatial weight matrix (W) to test the spillover effects of digital travel vouchers and other explanatory variables in model (3). The results reported in Tables 8 and 9 include results using the geographical adjacency matrix (\({W}_{{ij}}^{a}\)) and the nested weight matrix (\({W}_{{ij}}^{{de}}\)), respectively. First, in both cases, the results of R2 and Sigma2 suggest that the models are well-fitted. The magnitude of rho generally implies significant and positive spatial spillover effects.

Table 8 The spatial spillover effects: using the geographical adjacency matrix.Table 9 The spatial spillover effect: using the nested weight matrix.

On average, the effect of the spatial lagged voucher value in one city (W×lnVALUE) on tourist inflows of its adjacent cities is shown to be significant and positive at the 1% level of significance. This indicates that the issuance of vouchers in one city contributes to boosting tourist inflows in neighboring cities, confirming our Hypothesis 3 that there exists a spillover effect of the benefits brought by the voucher campaigns based on our sample data. The direct effect refers to the change in tourist inflows caused by local issuance of vouchers, while indirect effect refers to the change in tourist inflows caused by vouchers issued by neighboring cities.

It is interesting to note that the spatial lagged city size, in terms of population, exerts significant and negative impacts on attracting tourists, meaning that a larger size of one city reduces tourist inflows to its neighboring cities. The negative coefficient of W×lnPOP directly reflects the pattern of tourist mobility in China and confirms the siphon effect discussed in the existing literature (Wang et al. 2020). Similar results are also found in infrastructure development, which also has negative impacts on neighboring cities. In general, the results using nested weight matrix (Table 9) are consistent.