“I’ve lived here for 26 years and I have to say this place has lost its charm,” says Alexis Hauser, pointing to the most beautiful waterfall I’ve ever seen.

On a scorching hot July morning in Lauterbrunnen, a Swiss village in the Bernese Alps, a tongue of a glacier leads down into fields populated by herds of bell-ringing cows. Over the centuries, Lauterbrunnen’s beauty has inspired Shelley and Byron, and in 1911, the teenage hiker John Tolkien, who later used the valley as the model for his legendary town of Rivendell.

But this idyllic landscape is now under threat. Lauterbrunnen is on the brink of overtourism, and the culprit is not Tolkien but TikTok. Selfie sticks are raised like soldiers heading into battle along the busy valley roads, long queues form in front of waterfalls, and drones buzz overhead.

Queue for a photo at Staubbach Falls in Lauterbrunnen

Katie Gatens (Sunday Times)

In recent years, Huether says, the town has become “overcrowded and overcommercialized.” Her employer, Air Glaciers, offers helicopter tours of the valley. “Sure, business is good,” she says, watching the bus lumber along the narrow highway. “But what about the quality of life for locals? They’re going crazy, because there are food trucks selling corn dogs.”

It’s a familiar story across Europe: Tourists, many of them Americans wielding their powerful dollar, are flocking to the continent in astonishing numbers. There are 65 percent more Americans visiting the EU than there were a decade ago. But it’s not just Americans: As affluent middle classes emerge in China, India and Brazil, more people are on the move.

International visitor numbers were 709 million last year, 22% higher than a decade ago. As the share of global wealth shifts from Europe to China, India and the Gulf, the lure of Europe’s beaches, museums, churches, designer shops and deep cultural heritage – the remains of nations that once ruled much of the globe – is proving irresistible, especially since the shackles of lockdown have been lifted.

Europe’s allure seems to be growing despite its declining economic and geopolitical fortunes. Mallorca is set to break its tourist numbers record for the third year in a row. In 2022, the island received 17 million visitors. This year, 20 million are expected, about 22 times the population of Mallorca. This weekend, British airports are expected to be the busiest of the year as British schools go on summer vacation, and we’re joining the fray.

This annual wave of visitors brings much-needed benefits – visitors are expected to spend £670 billion this year – but it also brings conflict.

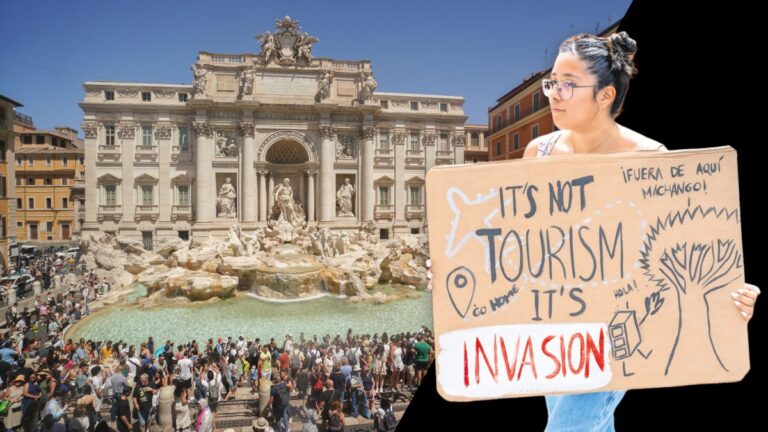

Violent backlash against overtourism has been brewing across the continent for years. Venice banned cruise ships and this year introduced a £4.20 entrance fee for tourists on its busiest days. Amsterdam announced a “total ban” on overtourism last spring, which means “no cruise ships, no new hotel construction and no more than 20 million tourist hotel nights per year,” according to the local government. Similar anti-tourist protests have emerged in many parts of Spain, including Athens, Lisbon, Venice, Barcelona, Mallorca and Tenerife.

Messages like this one, scrawled on Venice’s water buses, are becoming increasingly common in pressure zones in Europe.

splash

So what is causing this surge? And are the people protesting it self-destructive NIMBYs or upstanding citizens protecting themselves from being overwhelmed?

The new Grand Tour

“Looking back at the 19th century, Ruskin [the English philosopher] “It was the British who lamented how quickly the Alps were becoming overrun with tourists,” says Lucy Lethbridge, author of The Tourist: How an Englishman Went Abroad to Find Himself. “In the 1820s it was a desolate place, dangerous to cross, but by the 1850s it was developing as a winter sports destination.”

Brits have been traveling abroad for leisure since the days of the Grand Tour, when Georgian and Victorian gentlemen embarked on cultural journeys across Western Europe as a rite of passage. But Lethbridge points out that it wasn’t until Thomas Cook developed package tours for small groups to France, Germany and Italy in the 1870s that the concept of a “holiday” became popular among the general public. Inevitably, this led to a snobbish attitude towards “British expatriates” among the holidaymaker class that persists to this day.

Sunset is selfie time for visitors to Oia, a village on the Greek island of Santorini.

Katie Gatens (Sunday Times)

The first paid holiday laws were passed in the 1930s, giving Britons the right to paid holidays, and the idea of ”doing nothing” holidays really took off after World War II. Before then, “it was morally repugnant to the likes of Thomas Cook to not use your leisure time for good,” says Lethbridge.

The real game changer was the arrival of low-cost air travel. Thirty years on from the easyJet revolution, Europe was hosting all kinds of bachelor parties and excursions. In 1955, a one-way ticket from New York to London on Trans World Airlines cost £222, or £2,561 in today’s money. Today the same trip costs around £390. Thanks to Airbnb, accommodation has become more flexible and affordable.

Add to this the rise of social media tourism: Thanks to the rise of Instagram and TikTok, more people than ever before are visiting the same places, eating at the same restaurants and taking photos at the same waterfalls.

Lauterbrunnen’s population swells from 2,400 to 6,000 in high season. Not as large as Venice, but still the village is strained by the strain. Some roads are unpaved, forcing people to walk along the roadway. “No trespassing” and “No photography” signs are posted on houses. Last month, villagers considered introducing a “day-tourist tax.”

While strolling through the village, we met a group of 20-year-old backpackers from California on a six-week trip: Lauren, Mila, and Micah. “About a year ago, we posted to each other on TikTok about how beautiful the Alps were, and five of us said we wanted to go,” Micah said. Next up, they plan to go to Paris, Vienna, and Prague. “Many of our friends had experienced the ‘European summer,'” Mila said.

Mila, Mika and Lauren aren’t the first group of Americans to travel to Europe for the summer.

As summer temperatures regularly top 40 degrees Celsius in southern Europe, Instagram-worthy Alpine valleys in Switzerland and Austria are becoming increasingly popular. In Hallstatt, Austria, a town so beautiful that China built a model of it, residents last year blocked off a key tunnel leading to the town.

But there is a dissonance here. Lauterbrunnen is one of many places that both welcomes and dislikes mass tourism. The tourist board promotes a digital hotspot trail on its website. “People show me photos and ask, ‘Where is this?’ They just want to recreate it,” Heuser says.

Tour guides say many visitors to Lauterbrunnen are looking to recreate scenes they’ve seen on Instagram.

Andrea Comi/Getty Images

Tom Dürer is Lauterbrunnen’s resort manager and grew up in the village. He has 105,000 followers on Instagram, where he posts cool videos and photos to nearly 300,000 followers on Lauterbrunnen’s tourism page. Last year, the village saw a record number of overnight guests, 330,000.

“I wasn’t surprised,” Dürer says when his Instagram became popular a few years ago – the valley is very photogenic. He denies claims that Lauterbrunnen has a problem with overtourism: “It gets a bit crowded in high season, but that’s better than the coronavirus pandemic.”[virus] “In the days when everything was empty,” he says, “people had to take out loans to survive. I’m happier in this time than I was in the other way around.”

“Tourists are amazed when we flock to the beach.”

The vociferous anti-tourism movement in Europe has a populist flavour, reflecting dissatisfaction with the cost of living, especially housing. Young Europeans seem particularly unhappy with the continent being transformed into a giant museum.

The Mallorcan campaign group, “Less Tourism, More Life,” is modeled on a similar movement in the Canary Islands, a center of Spain’s anti-tourism movement. Pere Joan, a 25-year-old student from Mallorca, said the group has stepped up its protests this summer because “the situation is no longer sustainable.”

In May, thousands of Mallorcan residents protested against the proliferation of holiday rentals.

Alan Dawson/Alamy

“Of course the tourists are surprised,” he says, having taken part in the “Occupy the Beach” protests. “We talk to them and try to explain why we are doing this. It’s not the tourists that are the problem, it’s the tourism model in the Balearics,” he says.

Mallorca thrives on tourism, but Joan says wealth is distributed unequally and doesn’t benefit residents. Families who have lived on the island for generations are being pushed off to make way for holiday rentals and villas. “We want the government to control flights and cruise ship arrivals,” Joan says, “and regulate home sales to non-residents.”

Despite local opposition, desire to visit places like Mallorca has never been greater, but are tourists really getting what they want from these trips? Lethbridge points out that many visitors think they’re experiencing the “authentic” – buying woven baskets in Spain or lace in Venice – but these are industries artificially supported by tourism. “Tourism kills what you want,” he says.

“It’s a dire situation for communities that rely on tourism as their main source of income, because tourism not only almost wipes out the vitality of these places, but in some cases artificially maintains that vitality.”

Those who feel they can no longer survive on today’s levels of tourism may also find they can’t survive without it. “It’s fun to imagine the Spanish coastline filled with people fishing, but it’s a lot easier to make a living from tourism, and you can make a lot more money,” Lethbridge says.

At least there may be hope for residents fed up with overcrowding. Lethbridge predicts this could happen naturally if binding climate targets mean an end to cheap airfares. “I also think we’ll see cities like Barcelona start taxing Airbnb heavily and raising accommodation prices,” she says. “Or maybe people will just get tired of crowding eventually.”

As the fighting rages in Lauterbrunnen, some people are blissfully unaware, enjoying what tourism is all about: a welcome escape from the everyday grind. On the mountain train to Wengen, I meet Charles Neal, an 80-year-old pastor from Chattanooga, Tennessee, who is on his 16th visit. He first came here in 1966 and has returned with his wife ever since. “I fell in love with this place,” he says. He shows me the screensaver on his cell phone, the view in front of us, but taken five years ago. “Physically it feels almost the same,” he says. “It’s untouched nature.”

This is his first trip abroad since the pandemic began, and he’s here with his children and grandchildren to show them the places he loves. “We’ve been planning this for over a year,” he says. “Yes, we will be back. Absolutely.”