This article was produced by National Geographic Traveller (UK).

The name ‘Silk Road’ evokes images of Marco Polo and endless camel caravans stretching from Beijing to Baghdad and on to the Venetian Lagoon. But the fact is there was no single, definitive trail. Rather, the Silk Road was an umbrella term for a web of trade routes between China and Europe formed over a period of around 1,600 years, from the second century BC to 1450. While these routes wound as far south as India and Southeast Asia, most of their traffic moved overland through the heart of Central Asia, over snowy passes and through scorching deserts. Routes changed over time as new warlords demanded higher taxes from caravans wanting to travel through their territory. Other times, it was because of dangers caused by brutal brigands capturing riches such as silk, tea, ivory and precious metals, and enslaving travellers. Relics of the era can be found across the region today — particularly in the Central Asian segments of the Silk Road.

Few merchants and travellers made the full journey from Europe to China, as most goods and gold changed hands many times at various points along the Silk Road. Similarly, today, travellers tend to approach the region in bite-sized chunks — travelling the full length would take longer even than Marco Polo’s famous 24-year, 13th-century journey.

History buffs and architecture lovers often focus on Uzbekistan, where preserved mosques and madrasas hide behind fortress walls, and Soviet-era architectural oddities can be found. Trekkers and mountaineers turn towards Kyrgyzstan, a country of snowy peaks and a proud nomadic heritage. Kazakhstan blends the two, with a few attractive Silk Road ruins and impressive landscapes that make it an easy choice to add to any itinerary. The legendary, mountain-backed Pamir Highway — one of the world’s most epic road trips and the northern segment of the ancient Silk Road, described by Marco Polo in the 13th century — lies mostly within Tajikistan’s borders, but travellers intent on seeing it will have to contend with access restrictions and safety concerns.

Itinerary 1: Silk Road Cities

Once major hubs for global trade and centres of cultural exchange, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan’s cities are now welcoming oases for history lovers, complete with ornate Islamic architecture and crumbling ruins.

A local makes his way to pray at the Kalon Mosque, big enough to house 10,000 people.

Photograph by Tuul and Bruno Morandi, Getty Images

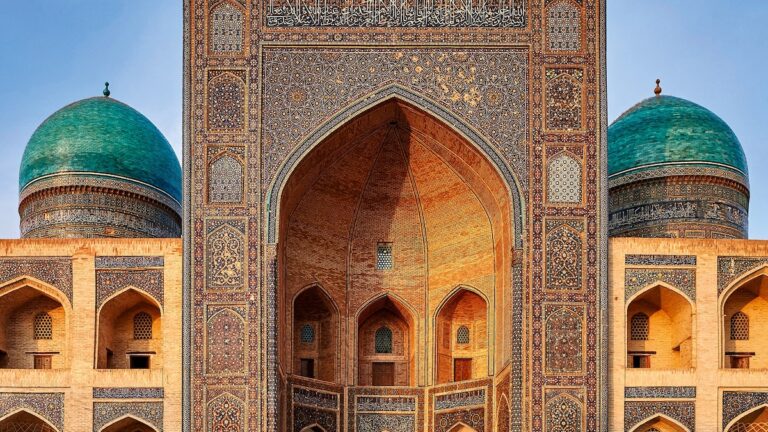

Twilight descends on the Mir-i-Arab Madrasa and Kalyan Minaret in Bukhara’s old town.

Photograph by Mlenny

Days 1-3

Arriving in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, board a train (13-17h) to Turkistan to explore the Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi. Dating to the late 14th century, it’s believed to be the earliest example of the Timurid architectural style — intricate tilework, multiple minarets and domes — that came to define the Silk Road. Set aside half a day to visit the partially excavated ruins of 10th-century desert fortress Sauran, 25 miles north west of Turkistan.

Days 4-7

Cross the border to Uzbek capital Tashkent, a pleasant city of parks and fountains that, with nearly three million inhabitants, is the biggest in Central Asia. The 18th-century Kukeldash Madrasah, built as an Islamic school, is one of the largest in Central Asia. Inside the nearby 16th-century Hazrati Imam complex is the world’s oldest surviving Quran, brought to Taskkent by Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur.From Tashkent, travel to Urgench by plane, bus or train (3h/14h/15h) and continue by shared taxi to Khiva (30min), the best preserved fortress city along the Central Asian Silk Road. The 2,400-year-old Itchan Kala (old town) is packed with ancient architecture; it would be easy to spend two days here, wandering the winding streets and climbing lofty minarets for views of the city.

Days 8-12

Go by train to Bukhara (6h) for three nights, then onward by train to Samarkand (1.5h). Both cities are UNESCO listed; Samarkand is the more famous, but Bukhara is the more appealing as it blends ancient and modern so well. Sixteenth-century trading domes are still in use, standing beside all-but-abandoned synagogues, family homes and bakers’ kiosks. In Samarkand, don’t miss the Gur-e-Amir, a mausoleum complex that contains the tomb of tyrant Timur, whose empire stretched from Aleppo to Delhi, and the imposing Registan — a plaza at the heart of the city that contains three ornately mosaiced madrasas. On the edge of the historic centre, the Shah-i-Zinda mausoleum complex, with its colourful, tiled facades, is also worth a visit.

Days 13-14

From Samarkand, add a trip to Shakhrisabz, Timur’s birthplace. Once envisioned as the capital of the Timurid Empire and eventual resting place of the conqueror, plans stalled when Timur unexpectedly died during a military campaign in 1405. Today, it’s a small, traditional town; just past a modern statue of Timur, the restored Chubin Madrasah has been converted into a museum dedicated to the tyrant and his empire.

Itinerary 2: Soviet Legacy

The Soviet Union ruled over much of Central Asia for more than half the 20th century, leaving an enduring physical and ideological legacy that can still be observed in the Silk Road nations of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

A vendor sells by a train station in Kazakhstan’s capital city of Almaty, which still reflects the Soviet era.

Photograph by Michael Charles Sheridan

Victory Square stands in the shadow of the Kyrgyz Range in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan’s capital.

Photograph by Jeremy Woodhouse, Getty Images

Days 1-2

Start in Almaty, exploring the history of Kazakhstan’s Soviet-era capital through the architecture and art of the era. A guided walk with the company Walking Almaty can be one of the best ways to uncover Modernist mosaics and Imperial-era buildings across the historic centre. In the mountains above the city is the modernist Medeu Highland Skating Rink, which opened in 1951. Soviet skaters broke more than 200 world records here before the USSR collapsed. It remains a popular venue, as well as an active competition venue.

Day 3-6

Travel west by car to Bishkek, across the border in Kyrgyzstan, where Soviet architecture surrounds a Lenin statue in the city centre. Just over an hour east of the city lies Issyk-Ata Sanatoria — a throwback to the Soviet-era hospital-spa-summer-camps, where tourists can stay overnight in dilapidated, pastel-blue dormitories. Guests can hike up the valley to a small waterfall (a three-mile round trip), returning for a dip in the sanatoria’s hot springs. Before returning to Bishkek, detour to Ata Beyit Memorial Complex, an hour west of Issyk-Ata. A secret mass grave of Soviet Kyrgyzstan’s intelligentsia was revealed here by a deathbed confession from one of the guards on duty the night of the massacre.

Day 7-10

It’s a nine-hour overland journey by bus or shared taxi via Kazakhstan — or a one-hour, 20-minute flight — from Bishkek to Tashkent in Uzbekistan. Rebuilt after a devastating 1966 earthquake, Tashkent today is still a showcase of Soviet modernism. Wander from the stone Monument to Courage Earthquake Memorial to the Islamic Modernist dome of Chorsu Bazaar and the brutalist facade of Hotel Uzbekistan. Then descend beneath the streets to ride the Soviet-era train carriages of the Tashkent Metro, where each of the 43 stations has its own distinct architectural style and artistic elements. Don’t miss a trip to see Physics of the Sun, a giant industrial solar furnace complex built by the Soviets in 1981 on a hilltop outside Parkent, 31 miles east of Tashkent. Brutalist in design and still operational today, it uses thousands of mirrored panels to channel heat from the sun.

Days 11-14

Finish your trip in the far west of Uzbekistan, with a long journey from Tashkent to the town of Nukus on the former shores of the Aral Sea — around 15 hours by car. This remote location is home to the Nukus Museum of Art, which displays collector Igor Savitsky’s world-class Soviet avant-garde art haul. Poor water management by the Soviets turned the Aral Sea (once the world’s fourth-largest lake) into a dust bowl, which can now be toured in a 4WD vehicle to see the carcasses of marooned ships. The barren scrublands are a devastating ecological warning as well as starkly beautiful. Independent visitors can arrange a bed for the night at Mayak Yurt Camp, which can also provide a driver for an unforgettable trip into the desert on the edge of the town of Moynaq, near the former shore.

Itinerary 3: Mountains & outdoor adventure

Lace up your hiking boots and head into the Tien Shan. The ‘heavenly mountains’ — a range that defines the border between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan — live up to their name, offering divine views of snow-capped peaks. There’s adventure here for every level of ability.

Two hikers rest on the trek to Ala-Kul lake. This three-day trail is Kyrgyzstan’s most popular, climbing to an altitude of 3,900 metres for epic views from the Ala-Kul Pass.

Photograph by Michael Charles Sheridan.

Days 1-4

From mountain-flanked Almaty in Kazakhstan, it’s a three-hour drive to 93-mile-long Charyn Canyon for hikes among red-rock towers and through labyrinthine gorges. The alpine village of Sati makes an ideal base for visiting the Kolsai Lakes. From the nearest lake, it’s an easy five-mile hike to the next, then a challenging two-and-a-half miles to the final one. Two valleys east, you’ll find Lake Kaindy; created by an earthquake in 1911, it contains a partially submerged forest of spruce trees, whose exposed tips make for a surreal sight.

Days 5-8

Cross the border into Kyrgyzstan and make for Karakol, founded in 1869 as a military outpost. Its wooden cottages are now interspersed with hostels catering to armies of hikers. The three-day trek to Ala-Kul lake is Kyrgyzstan’s most popular, climbing to an altitude of 3,900 metres for epic views over the lake from the Ala-Kul Pass. At the end of the trek, visitors can hire a Soviet-era military truck for a day trip to the Altyn-Arashan springs to sooth sore muscles.

Days 9-11

Hike around Issyk Kol lake, staying at lakeside yurt camps such as Feel Nomad or Bel-Tam. Support conservation initiatives on a guided hike of Baiboosun Nature Reserve or make the easy, one-mile hike to the Shatyly Panorama for views over Issyk Kol and the snowy Tien Shan peaks.

Days 12-14

Continue to Song-Kol lake at a breathtaking 3,015 metres. Drive up in around four hours from Kochkor on Issyk Kol’s western side, or take one to two days hiking and horse-trekking there from Kyzart, 45 miles west of Kochkor. Spend a full day at the lake, horse-riding through the grasslands in solitude. Afterwards, drive to Bishkek for day hikes up the forested slopes of nearby Ala Archa National Park or to explore the Soviet architecture of the capital.

How to travel: a practical guide

What visas will I need for Central Asia?

Visa policies have loosened considerably over the last decade, with travellers on UK passports currently allowed visa-free entry to Kazakhstan (30-day stay), Uzbekistan (30 days) and Kyrgyzstan (60 days). Longer stays will still require a visa, which must be issued at an embassy or through each country’s e-visa platform. You still need a visa to enter Tajikistan, which can be applied for online before arrival (avoid the on-arrival service, which is a frustrating, time-consuming process).

Am I likely to need any travel permits?

Trips to some remote border regions of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan do require special permits. If your itinerary includes the Pamir Highway in Tajikistan, for example, you’ll need a permit from the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, and it’s best to apply for it with your initial country visa application to save time. Applying for permits can involve Soviet-style bureaucracy; if travelling independently, it’s worth paying a local tour company to do it on your behalf. Fees are usually £25 to £40 per permit.

How should I manage money while travelling?

Credit cards are widely accepted in Central Asia’s cities but rarely outside of them, and even in cities you’ll still need cash for small purchases. ATMs are widespread in the big cities, but they can unexpectedly run out of cash — particularly on weekends — so it’s worth also carrying some foreign currency. British pounds and Euros can reliably be changed in cities, but in towns and rural areas US dollars are the easiest to exchange.

What languages are spoken across the Central Asian Silk Road?

Russia is the common language in this region. Tourism businesses in popular destinations will usually have English-speaking staff; it’s harder to find English speakers in rural areas.

How should I dress while travelling here?

Locals across the region typically dress more conservatively than in the West. While visitors aren’t usually expected to adhere to local norms, you may be the target of unwanted attention if you don’t cover your shoulders and knees, especially in rural areas; the capital cities across Central Asia tend to be more liberal.

Getting there & around

The only direct flights from the UK to Central Asia depart from Heathrow. Uzbekistan Airways connects to Tashkent twice a week (7h) and Air Astana flies to Aktau in Kazakhstan five times a week (6h). Both airlines offer onward connections within the region to all the national capitals and a selection of smaller cities. Lufthansa flies from the UK to both Almaty and Astana in Kazakhstan via Frankfurt (four weekly, 6-7.5h). Alternatively, fly Turkish Airlines from Manchester or London to Istanbul to connect onwards to 14 airports within the region.

Public bus and minibus networks run within every major city, while Tashkent and Almaty both have metro systems. Between cities, set-route minibuses or shared taxis cover nearly all cities and towns. Across Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, taking a train is usually the best option, where they exist, although internal flights across Kazakhstan can save considerable time.

In Uzbekistan, high-speed rail connects Tashkent to both Samarkand and Bukhara and is set to be extended to Khiva by 2024. Prices vary by route, but expect to pay around £12 for the 3.5h trip from Tashkent to Bukhara; some longer services (such as Astana to Almaty: 16h) have cabins. Elsewhere in both countries, a wider network of Soviet-era services still runs. Book tickets at least three or four days in advance, as they often sell out.

When to go

April to May are ideal months for cultural tourism across the region, with spring rains finished and daytime temperatures pleasant in the lower elevations of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan (highs 24-31C), though mountainous areas will still be cold. July and August are ideal for hiking and horseback riding, but Tashkent, Samarkand, Bukhara and even Bishkek will be sweltering, with temperatures around 35C. October and November see heavy rains and the first snows. Winter is popular for ski holidays near Almaty, Bishkek, Karakol and Tashkent, but the region’s cities are choked by smog at this time of year — stay in the mountain resorts wherever possible.

More info

caravanistan.com

indyguide.com

Lonely Planet Central Asia. RRP: £19.99.

Published in the June issue of National Geographic Traveller (UK).

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).